|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|||||

| . . . Stephen Crane | |||||

| . . . 2000-11-15 |

The Red Pencil of Courage

The innate human need to muck around lies behind most revised-and-corrected editions, but it's an unusual editor these days that explicitly relies on whim: modern scholars figure they have to follow some explicitly stated rule instead.

Which just passes the burden of whimsicality on to historical gaps in one direction and on to the purchaser in the other. Do we choose the last thing that we're pretty sure the author had their personal hands on? Or the last thing there's no evidence of the author objecting to? Or do we throw everything up in the air and let the hapless reader pick and choose?

Stephen Crane was a fast and hungry writer who didn't seem too interested in yesterday's papers. So inasmuch as anyone cares to justify an editorial approach by biography rather than whim, the final extant manuscript of The Red Badge of Courage might have an edge over the final published version of The Red Badge of Courage. But whim will have its way, and the choice of editorial rule pretty much depends on which version the editor likes more. Henry Binder liked the one that was sent to the publisher; J. C. Levenson liked the pared-down one that got published.

An entire introspective chapter and big introspective chunks of others were taken out, mostly devoted to watching Henry Fleming's self-image swing from self-abasing flagellation to Byronic villainy and back again. Pretty funny stuff, but, yeah, repetitious over the long haul; if Crane had been interested in revision, these would've made good targets. But, more importantly, the mood of the book's last chapter was shifted from viciously ironic to inspiringly upbeat:

| . . . 2023-04-27 |

In youth, poetry and fancy prose styles were my best entertainment values. I didn't have to scrape up the cash for subscriptions consisting mostly of throwaway ads, or LP box sets and a constantly upgraded quadraphonic hi-fi system, or season seats in arenas or concert halls. I could lazily, at my own pace, check books out from the library, occasionally buy cheap paperbacks, and that was that.

Well, as the poet sang, "I ain't gonna be eighteen again, I know it." After the harrowing of browsable paper volumes from public library shelves, and the deforestation of used bookstores, and a series of copyright enclosures around any edition less than a century old, attaining a taste for poetry might be as expensive a prospect as it was in the years of parchment.

But wait! There's hope! Or at least an opportunity for massive corporations to leverage artificial scarcity to extract high profits from publicly funded institutions, which five out of five politicians agree is even better than hope. Ask your publicly funded institution about ProQuest LION (short for "Literature Online", in the sense of "Roach Motel"):

Right now, the subscription packages Proquest and Ebsco offer may sound like they cost a lot (between $500-$800,000 a year), but the price is “extremely low relative to the number of books acquired,” to quote the CSU report on the e-book pilot project.

The report understated its case. ProQuest doesn't merely acquire "primary texts"; it augments them. First it rips all the pages out of a book, discards some, and shuffles the rest. And then it defaces each past the point of easy readability. Imagine how much you'd have to pay a mob of Republican goons for that kind of service.

The damage is hardest on otherwise unavailable poetry, of course, but since I don't want mean old Mr. Hachette's gang coming after me I'll illustrate from the public domain: Stephen Crane's first collection of peculiar versicles, The Black Riders, and Other Lines.

The Hachetted Internet Archive still provides a facsimile of its 1905 edition:

Project Gutenberg has well-OCRed HTML and EPUB versions:

ProQuest sources the poems from a scholarly edition (shorn of all scholarly apparatus) but the contents match:

![Contents: 136 items, beginning with [I. Black riders came from the sea]](images/Proquest-Crane-contents.png)

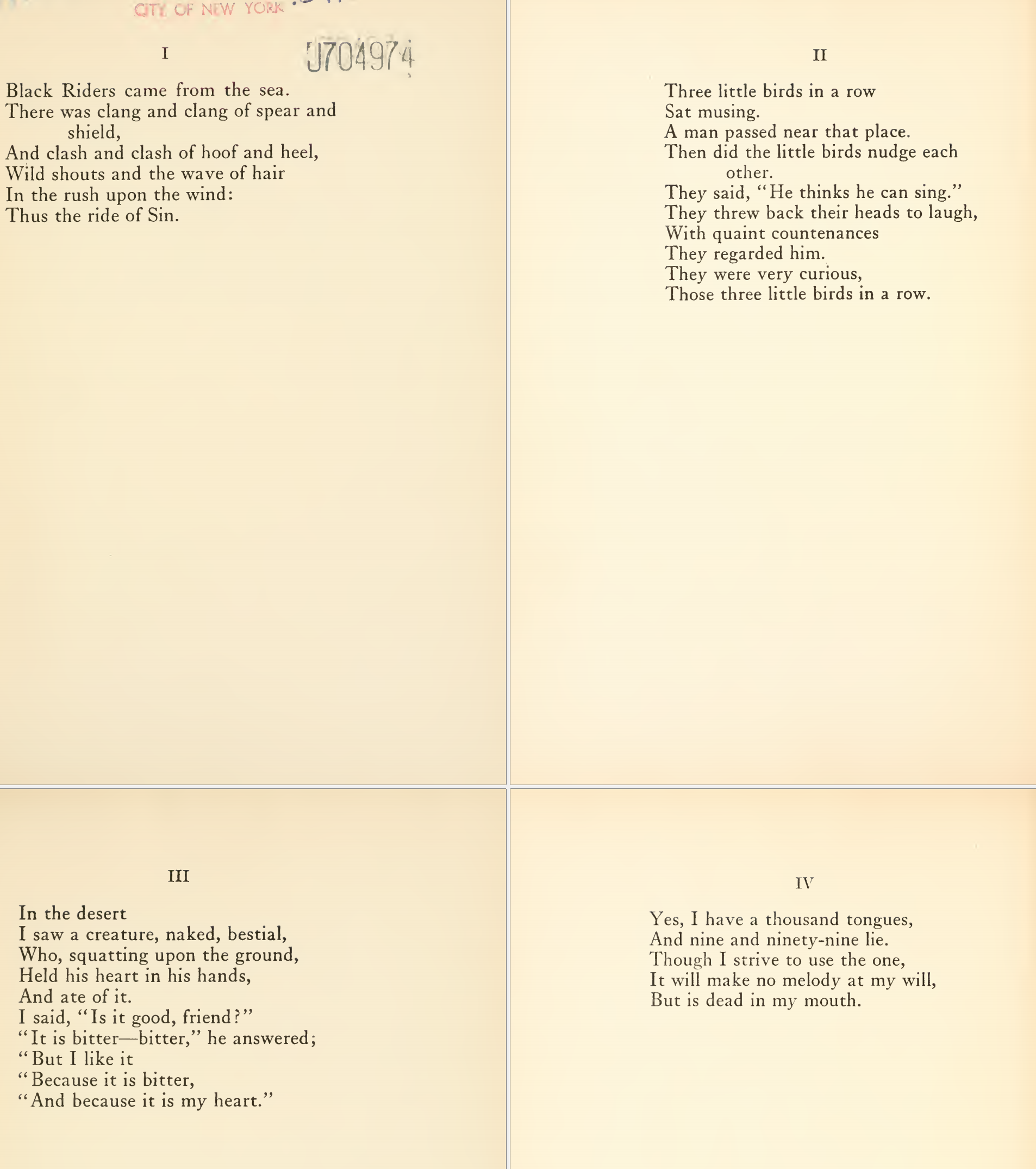

So we just need to select the first batch, download a PDF, open it, and start reading:

![Huge gobs of boilerplate noise around number-prefixed verse sections, beginning with [XIX. A god in wrath]](images/Proquest-Crane-first-poems-in-PDF.png)

After many tries over many books, all I can make of ProQuest's ordering algorithm is that it resolutely ignores page numbers.

Line numbers, on the other hand! A Comp. Sci. major must've opened their Norton's anthology, seen familiar digits unobtrusively appended at a polite distance every five or ten lines, and decided those were the best parts. Words are afterthoughts.

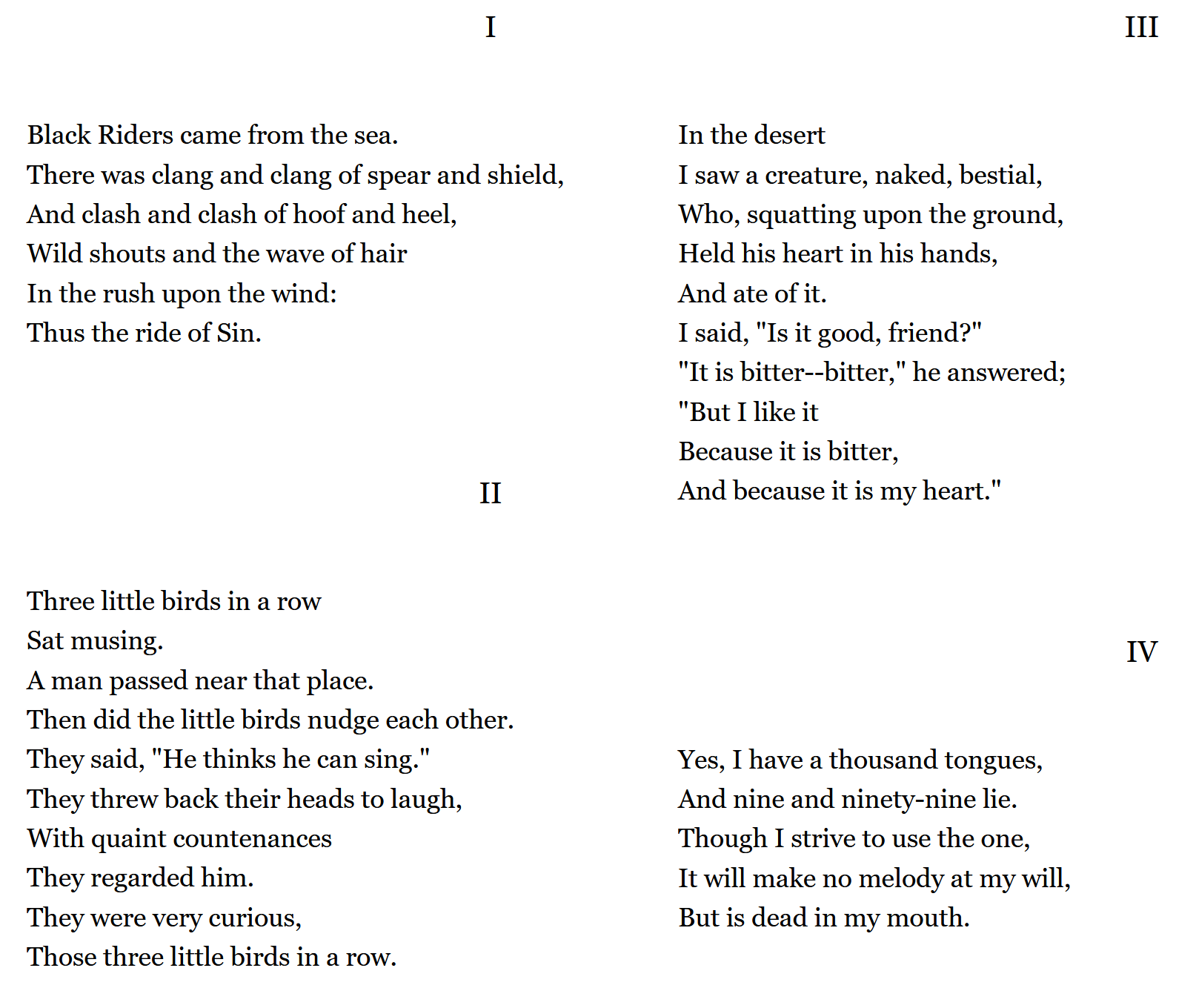

ProQuest's save-&-export options include "Text only", which sounds promising but looks like so:

![Huge gobs of boilerplate noise around number-prefixed verse sections, beginning with [XIX. A god in wrath]](images/Proquest-Crane-first-poems-in-text.png)

Not much gained, except for gluing the title to the first line of verse.

To wax professional for a moment, there's no Javascript task more basic than toggling the visibility of a particular sort of text. And if memory serves me well, when I first encountered "LION" twenty-or-so years ago, a button was provided to remove those numbers. Nevertheless, at some point some unknowable dysfunctionary, presumably tasked with adding more boilerplate branding and fuckall else, learned it wasn't worth the effort.

Must be fun for screen-readers.

Now, I'm just a simple country boy who won a library card in a Bingo game, not a department head, nor an emeritus doctor of physic nor philosophy, nor a donor ripe for money-debagging. But maybe somewheres up thar in the whirly starry spheres, someone with actual influence actually gives a shit about getting something useful from their investment?

Copyright to contributed work and quoted correspondence remains with the original authors.

Public domain work remains in the public domain.

All other material: Copyright 2015 Ray Davis.