|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| . . . 2018-10-28 | ||||||

Mojo Hand : An Orphic Tale by J. J. Phillips

1. "Eurydice's victims died of snake-bite, not herself." - Robert Graves

Protagonist "Eunice" is, as we can plainly see, an un-dry Eurydice. And love-object Blacksnake Brown is Orphic because he sets the stately oaks to boogie:

She went to the phonograph there and looked through the stack of records under it. Down at the bottom, dusty and scratched, she found an old 78 recording called “Bakershop Blues” by a man named Blacksnake Brown, accompanied by the Royal Sheiks. She lifted off the classical album, slipped on the 78, then turned the volume up. It started scratching its tune.I want to know if your jelly roll’s fresh, or is it stale, I want to know if your jelly roll’s fresh, or is it stale? Well, woman, I’m going to buy me some jelly roll if I have got to go to jail.

Almost immediately she heard shouts and shrieks from the other room.

“. . . Oh, yeah, get to it. . . . Laura, woman, how long since your husband’s seen you jelly roll?”

“Gertrude, don’t you ask me questions like that. Eh, how long since your husband’s seen you?”

Eunice went back downstairs. Everyone had relaxed. Some women were unbuckling their stockings, others were loosening the belts around their waists. Someone had gotten out brandy and was pouring it into the teacups.

“Give some to the debs,” someone said, “show them what this society really is.”

Just as plainly, though, "Blacksnake" is a snake, with an attested bite. And for all l'amour fou on display, Eunice is only secondarily drawn to her Orpheusnake; first, last, and on the majority of pages in-between, she's after Thrace-Hades:

And even before that she had been drawn to the forbidden dream of those outside the game, for they had been judged and did not care to concern themselves with questioning any stated validity in the postulates. Playing with friends, running up and down the crazily tilted San Francisco streets, they would often wander into the few alleys between houses or stores down by the shipyards. [...] The old buildings were not of equal depth in back, nor were they joined to one another, and there were narrow dark passageways between the buildings. She would worm her way in and out of these, for they were usually empty, though occasionally as she would whip around a corner she would hear voices and would tiptoe up to watch two or three men crouched on the ground, each holding a sack of wine, and shooting dice. She would hide and watch them until the sun went down, marking their actions and words, then tramp home alone whispering to herself in a small voice thick with the sympathy of their wine, “Roll that big eight, sweet Daddy.”

This place which is also a community and a way of living — maybe a good name for that would be habitus? — although nowadays and hereabouts ussens tend to call it an identity. To switch mythological illustrations, what Odysseus craved wasn't retirement on a mountainous Mediterranean island, or reunion with his wife and child, both of whom he's prepared to skewer, but his identity as ruler of Ithaka.

What baits Eunice isn't so much the spell of music but the promise of capture and transportation. Brown's a thin, helpfully color-coded line who can reel her out of flailing air and into Carolina mud, a properly ordained authority to release her family curse (and deliver her into bondage) by way of ceremonial abjuration:

“We-ell, you being fayed and all, I doesn’t want to get in no trouble.”The night was warm and easy, and it came from Eunice as easy as the night. “Man, I’m not fayed.”

He straightened up and squinted. “Well, what the hell. Is you jiving, woman, or what? You sure has me fooled if you isn’t.”

“You mean you dragged me out in the middle of the night into this alley just because you thought I was fayed? That’s the damndest thing I’ve ever heard.” But she knew it was not funny, neither for herself nor for him.

Blacksnake broke in on her thoughts. “Well, baby, if you says so, I believes you. But you sure doesn’t look like it, and you doesn’t even act like it, but you’s OK with me if you really is what you says you is. Here, get youself a good taste on this bottle.”

Eunice took the bottle and drank deeply, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand.

(In many more-or-less timeless ways, Mojo Hand is the first novel of a very young writer. On this point of faith, though, it's specifically an early Sixties novel: that the Real Folk Blues holds power to transmute us into Real Folk.)

2. "Meet me in the bottom, bring my boots and shoes." - Lightnin' HopkinsHaving passed customs inspection, Eunice considers her down-home away from home:

Until this night she had been outside of the cage, but now she had joined them forever.

About twenty-hours later, "the cage" materializes as a two-week stretch in the Wake County jail:

But soon she came to learn that it was easier here. Everything was decided. That gave her mind freedom to wander through intricate paths of frustration.

Jail isn't a detour; it's fully part of Eunice's destination, and afterward she's told "Well, you sure as shit is one of us now." But what sort of freedom is this?

Some people intuit a conflict between "free will" and "reasoned action." (Because reasons would be a cause and causality would be determinism? Because decisions are painful and willful freedom should come warm and easy?) Or, as Eunice reflects later, in a more combative state of mind:

Since her parents had built and waged life within their framework, in order to obvert it fully she, too, had to build or find a counterstructure and exist within it at all costs. The difference lay in that theirs was predicated on a pseudo-rationality whereas the rational was neither integral nor peripheral in hers; she did not consider it at all. To her the excesses of the heart had to be able to run rampant and find their own boundaries, exhausting themselves in plaguing hope.

When the pretensions of consciousness become unbearable, one option is to near-as-damn-it erase them: minimize choices; make decision mimic instinct; hand your reins to received stereotype and transient impulse. Lead the "simple" life of back-chat, rough teasing, subsistence wages, steady buzz, sudden passions, unfathomable conflicts, limitless boredom, and clumsy violence. A way of life accessible to the abject of all races and creeds in this great land, including my own.

All of which Phillips describes with appropriately loving and exasperated care, although she's forced to downshift into abstract poeticisms to traverse the equally essential social glue of sex.

It was completely effortless, with the songs on the jukebox marking time and the clicking pool balls countersounding it all until the sounds merged into one, becoming inaudible. Eunice felt the ease, the lack of rigidity, and relaxed. She would learn to live cautiously and underhandedly so that she might survive. She would learn to wrangle her way on and on to meet each moment, forgetting herself in the next and predestroyed by the certainty of the one to come.

3. "At the center, there is a perilous act" - Robin Blaser

In this pleasant fashion uncounted weeks pass. Long enough for a girl to become pregnant; long enough for whatever internal clock ended Brown's earlier affairs to signal an campaign of escalating abuse which reviewers called mysterious, although it sounded familiar enough to me.

Blacksnake was Eunice's visa into this country. What happens if the visa's revoked? If our primary goal is to stay put and passive, what can we do when stasis becomes untenable?

Shake it, baby, shake it.

Having escaped into this life, Eunice refuses to escape from it:

There was no sense, she knew, in going back to San Francisco, back home to bring a child into a world of people who were too much and only in awe of their own consciousness. They were as rigid and sterile as the buildings that towered above them.

She'll only accept oscillation within the parameters of her hard-won cage. This cul-de-sac expresses itself in three ways:

It seems perfectly natural for the strictly-local efficacy of the occult to appear at a crisis of sustainability, scuffing novelistic realism in favor of keeping it real. The flashback, though, rips the sequence of time and place to more genuinely unsettling effect, and Phillips handles the operation with such disorienting understatement that this otherwise sympathetic reader sutured the sequence wrong-way-round in memory.

It's unsettling because we register the narrative device as both arbitrary and, more deeply, necessary. Being a self-made self-damned Eurydice, Eunice must look back at herself to secure permanent residence. But when the goal is loss of agency, how can action be taken to preserve it?

Instead, we watch her sleepwalk through mysteriously scripted actions twice over.

4. "Black ghost is a picture, & the black ghost is a shadow too." - Lightnin' Hopkins

Immediately after you start reading Mojo Hand, and well before you watch Eunice Prideaux hauled to Wake County jail, you'll learn that J. J. Phillips preceded her there. If you're holding the paperback reissue, its behind-bars author photo will have informed you that both prisoners were light-skinned teenage girls.

If you've listened to much blues in your life, you'll likely know "Mojo Hand" as a signature number of Lightnin' Hopkins. If you've seen photos of Hopkins on any LPs, the figure of "Blacksnake Brown" will seem familiar as well.

Since comparisons have been made inevitable, contrasts are also in order.

Blacksnake Brown is clearly not the Lightnin' Hopkins who'd played Carnegie Hall, frequently visited Berkeley, and lived until 1982. Eunice is jailed for the crime of looking like a besmirched white woman in a black neighborhood at night; Phillips, on the other hand:

In 1962 I was selected to participate in a summer voter registration program in Raleigh, North Carolina, administered by the National Students Association (NSA). [...] Our group, led by Dorothy Dawson (Burlage), wasn't large and the project was active only for that summer; but during the short time that we were in Raleigh, we managed to register over 1,600 African Americans, which, along with other voter registration programs in the state, surely helped pave the way for Obama's 2008 victory in North Carolina. [...] On the spur of the moment I'd taken part in a CORE-sponsored sit-in at the local Howard Johnson's as part of their Freedom Highways program, which took place the year after the Freedom Rides. [...] Our conviction was of course a fait accompli. We were given the choice of paying a modest fine or serving 30 days hard labor in prison; but the objective was to serve the time as prisoners of conscience, and so we did. In deference to my gender, I was sent to the Wake Co. Jail.[...] Thus began a totally captivating 30 days — an immersive intensive in which I got the kind of real-life education I could never have obtained otherwise.

This unexpectedly welcome "captivation" brings us back to Eunice, however, and thence to Eunice's own brush with voter registration programs:

“I don’t want to register.”The boy shifted from one flat foot to another and scratched a festering pimple. “But ma’m, it’s important that you try and better your society. Can’t you see that?”

“No, I can’t.”

He paused a moment, and then proceeded. “Whatever your hesitation stems from, it is not good. It is necessary for us all to work together in obtaining the common goal of equality. It is not only equality in spirit; your living standards must be equal. Environment plays an important factor. You must realize also that it is not only your right but your duty to choose the people you wish to represent you in our government. If you do not vote you have no choice in determining how you will live.”

Eunice chuckled as she remembered Bertha back in the jail. She crinkled her eyes and laughed. “Well, sho is, ain’t it.”

In turn, that "festering pimple" suggests some animus drawn from outside the confines of the book. And in an interview immediately following the book's publication, its author came close to outright disavowal:

"I went to jail to see what it was like. I was in Raleigh on a voter registration drive. Somebody asked for restaurant sit-in volunteers sure to be arrested. I was not for or against the cause, I just wanted to go to jail." [...] Slender, with the long, straight hair, wearing the inevitable trousers, strumming the guitar, she also defies authority in her rush to individual freedom. She lives in steady rebellion against the comfortable — escapist? — atmosphere provided by her parents, both in professional fields and both successful. Her own backhouse, bedroom apartment, her transportation — a Yamaha and a huge, black, 5-year-old Cadillac; her calm acceptance of her right to live as she pleases are all a part of the pattern of the new 1966 young.

(For the record, yes, I'm grateful that no one is likely to find any interview I gave at age 22, or to publish any mug shot of me at age 18.)

Forty-three years later, J. J. Phillips positioned Mojo Hand in a broader context: three separate cross-country loops during an eventful three years which she entered as an nice upper-middle-class girl at an elite Los Angeles Catholic college and left as an expelled, furious, disillusioned, blues-performing fry-cook.

Which of these accounts should we believe? Well, all of them, of course. Here, what interests me more is their shared difference from the story of Eunice.

* * *

The older Phillips summarized Mojo Hand as "a story of one person’s journey from a non-racialized state to the racialized real world, as was happening to me."

As always, her words are carefully chosen. In the course of a sentence which asserts equivalence, she shifts from Eunice's singular, focused journey to something that "was happening to" young Phillips. More blatantly, she tips the balance by contrasting "a state" with "the real world."

Contrariwise, someone might describe my own wavering ascent towards Eunice's-and-Phillips's starting point as "one person's journey from a racialized state" (to wit, Missouri) "to the class-defined real world." I'm not that someone, though. Even at the age of Mojo Hand's writing, when my scabrous androgyny was demonstrably irredeemable, I understood that, should I live long enough, my equally glaring whiteness would bob me upwards like a blob of schmaltz. And indeed, although my patrons and superiors have been repeatedly nonplussed by my choices, none ever denied my right to make them.

Whereas, in America, some brave volunteer or another can always be found to remind you that you're black or female. And in the ordinary language of down-home philosophizin', if you can't escape it, it's real: truth can be argued but reality can only be acknowledged, ignored, or changed. Even if "race" is an unevidenced taxonomy and "racism" is a false ideology, "racism" and "a racialized world" remain real enough to kill — depending on time and place.

As does "class." And, like Phillips in Los Angeles, in San Francisco Eunice was born into a particularly privileged socio-economic class. Even if she'd stayed in San Francisco, she could've chosen to remove herself from that class, most likely temporarily, anticipating the "inevitable pattern of the new 1966 young." But merely by having the choice, she would have become in some sense, in some eyes, a fraud.

The Jim Crow South, however, offered any stray members of the striving class at most the choice of "passing," faudulent by definition. Thus, with the mere purchase of a train ticket, properly propertied individuals could reinvent themselves as powerless nonentities. What racialized Eunice and Phillips was travel to a place in which no non-racialized reality existed. What made that racialization lastingly, inescapably "real" was, for Eunice, a permanent change of residence. For Phillips, back in California, it was recognizing a racism which had previously stayed latent or unnoticed, and which continued to be denied in infuriatingly almost-plausible fashion.

5. "But I didn't know what kind of chariot gonna take me away from here." - Lightnin' Hopkins

Returning to the book's one encounter with progressive politics, after Eunice shuts the door on the pimpled young man, Blacksnake is bemused (not for the first time) by her volitional assumption of a cage in which others were born and bred:

“Oh, shit. Woman, I can’t vote. I been to the penitench. [...] Girl, you got some strange things turning ’round in that head of yours. Why did you come here anyway?”“I don’t know. I just felt like it.”

Eunice sat down on the bed and scratched her head. It was useless to try and find the causes of her being here; she merely was and could never be sure whether it was a true act or a posture of defiance.

Odysseus traveled to reclaim his prior identity. How, though, would someone establish an identity?

By fiat, by fate. With that infallible sixth sense by which we know we were a princess dumped on a bunch of dwarfs, or the infant who was swapped out for a changeling, Eunice knows she's been denied her birthright. Or two birthrights, which Mojo Hand merges:

First, racialization; that is, membership in a race.

Second, the inalienable right and incorrigible drive to make irretrievable mistakes and trigger fatal disasters. In a word, maturity.

Never had she been forced to her knees to beg for the continuation of her existence, nor fight both God and the devil ripping at her soul; never had she been forced to fight to move in the intricate web of scuffle; never had she been forced to fight a woman for the right to a man, nor fought out love with a man. She had never fought for existence; now she would have to.

In well-ordered middle-class mid-century households, these are things parents protected children from, things children couldn't imagine their parents doing. Most of them are part of most adult lives, and once experienced, they're not likely to be forgotten. But depicting them comes easiest when they're assigned to disorderly elements, and a narrative's end is more attended than its torso.

In the novel's introductory parable, a girl who finds the sun (dropped by an old-fashioned Los Angeles pepper tree) is forced by her father to give it up. During her longest residence in Lightnin' Hopkins's Houston neighborhood, Phillips met similar interference: "I especially did not want to suffer the ultimate mortification of being ignominiously carted home by my parents, so I went back to L.A."

If Eunice had been dragged back to San Francisco, that anticlimax would be interpreted as an ironic deflation of a hard-won life. And so, in vengeance for her parents' deracination, Eunice is silently de-parented, and the book instead ends with her both adopting a new mother and waiting to become a new mother.

* * *

The United States between 1962 and 2009 incorporated a whole lot of habitussles, each with its own preferred ways to swing a story. Even as something is done (by us, to us, of us, the passive voice is the voice that rings real) — and certainly afterwards — we're spun round by potential justifications, motives, excuses, bars, blanks.... Whichever we choose, sho is, ain't it.

One year after 22-year-old J. J. Phillips saw Mojo Hand in print, 25-year-old Samuel R. Delany saw his own version of black Orpheus, A Fabulous, Formless Darkness, published as The Einstein Intersection. Neither fiction much resembles Ovid, and where Phillips mythologizes black community, Delany mythologizes queer difference. What the two writers shared was a reach for "mythology" as that which both describes and controls the actions of the mythological hero: a transcript which is a script; a fate justified as fulfillment of fate.

A story to make sense of senselessness and reward of repeated loss.

What Phillips suffered and enjoyed as an indirect, experimental process of frequently unwelcome discovery and retreat, confrontation and compromise, Eunice is able to consciously hunt as a coherent (if not rationally justifiable) destination. The mythic heroine's one necessary act of mythic agency was to decide to enter that story and, mythically, stay there ever after. The oaks rest in place, thoroughly rooted, frozen in their dance.

Lucky oaks.

| . . . 2018-10-30 |

In fake news which stays fake news, the Repress has recently added a second self-parody by Algernon Charles Swinburne to its collection. Less a stylistic attack than a personal one, it combines Swinburne's three favorite things: verse, flagellation, and the ocean. He shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach....

| . . . 2018-10-31 |

I used to describe Ruben Bolling as "Tom Tomorrow except funny." Now I view him through a more beatified glow, like a cross between Herblock and St. Cassian (except funny), the one public voice perceptive and honest enough to have frozen into a continuous throat-shredding scream of disbelief and horror. How better to enjoy Hallowe'en than with his remake of Gaslight?

But, as Dr. Josh Lukin knows, nothing scares me more than dissent:

And a voice said, Nah, nah! You thought it was good...

| . . . 2018-11-12 |

The Death of Democracy:

Hitler's Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic

by Benjamin Carter Hett

Having reviewed the latest evidence, Dr. Hett declares that the Republic's demise was not the inevitable result of Versailles terms (which weren't notably harsher than those dictated to France in 1871, and which were softened over time), or the global Great Depression (for which he assigns German leaders more responsibility than I've seen before), or Joel Grey camping it up.

Instead, the killing blow came after years of poisoning by the Reich's established pre-Armistice powers — the wealthy, the propertied, the generals — who would do anything to protect that power from the ignorant mob. For the good of the nation, of course, only for the good of the nation; it's a sad noblesse oblige that the good of the nation so invariably depends on propping up its existing executive class. I believe that truism also guided Allied reapportionment of power after V-E Day.

Even as the Great War was being concluded, Hindenberg and other conservatives entered on (or in good conservative fashion continued) a policy of self-serving deceit and conspiracy. (Because it's not an Unseen Hand if you actually see it picking your pocket.) And they continued to rely on those well-established techniques, rejecting or sabotaging any actions whose success might rebound to the political benefit of the left, until they encountered a group far more dedicated to and skilled at deceit and conspiracy.

My favorite bit — apologies for the spoiler — came when General Kurt von Schleicher collaborated with the Nazis to bring down Prussia's popular Social Democratic administration through a combination of fradulent reporting (James O'Keefe avant la vidéo) and manufactured emergency.

Whereupon the Nazis threatened to reach way, way across the aisle to help Communists bring down the national administration on the pretext that "Hindenberg had acted illegally in ordering the Prussian coup." Lie down with wolves, get up with your face eaten off.

Hett's convincingly dismal account ends with the usual attempt at a pick-us-up:

Few Germans in 1933 could imagine Treblinka or Auschwitz, the mass shootings of Babi Yar or the death marches of the last months of the Second World War. It is hard to blame them for not foreseeing the unthinkable. Yet their innocence failed them, and they were catastrophically wrong about their future. We who come later have one advantage over them: we have their example before us.

He seems like a sincere, unsarcastic sort of guy, and so he probably didn't intend me to immediately recall his books's chief example of someone learning from history:

Twelve years later, on April 27,1945, as the Soviet Red Army closed in on his Berlin bunker, Hitler chatted about old times with his loyal propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, and an SS general named Wilhelm Mohnke. [...] Mohnke commented, “We haven’t quite done what we wanted to do in 1933, my Führer!” Hitler seemed to agree, and he gave a surprising reason: he had come to power a year and a half too soon. [...] Coming to power when he did, with Hindenburg still alive, he had had to make deals with the conservative establishment. “I had to wriggle from one compromise to another,” Hitler complained. He had been forced to appoint many officials who were not reliable, which explained why there had been frequent leaks of information. Hitler also said that he had planned to bring “ruthlessly to account” people such as Hammerstein, Schleicher, and indeed “the whole clique around this vermin.” But after eighteen months in office he had grown milder, and in any case, the great upswing in Germany’s economic and political fortunes was under way. “You regret it afterwards,” Hitler said, “that you are so kind.”

| . . . 2019-02-10 |

Dear Hollywood, I sympathize, I know you must butter up for greased palms to trickle down; I know MBAs make the world go brown. But Hollywood, on behalf of those negligible folk who mean well yet are neither Forrest Gump nor Dexter, FYI:

Sociopaths are no more remarkably intelligent than they're remarkably ethical. They merely follow impulses which waste the time and ruin the lives of intelligent and ethical people around them. They're not master puzzlemakers laboring to gift us a masterpiece puzzle. They're white noise generators asking us to derive a signal.

Dr. Lecter, Professor Moriarty, Herr Gruber, Kevin Spacey — how different from the home life of our own dear Queen, who learned everything he needed to know in kindergarten: "I'm rubber, you're glue" and Roy Cohn's phone number.

Josh Lukin advances the narrative:

This romanticization of sociopaths must be why the movies billed Parker, of all people, as "a thief with a unique moral code." Well, that and the inability to distinguish a moral code from a management strategy.

House Republicans been schooled:

| . . . 2019-02-20 |

The credits claim this is a Clouzot script directed by Chabrol, but it's actually Kiss Me, Stupid as interpreted by Frank Tashlin. Blanket misanthropy conveyed through vividly immersive cartoonishness turns out to provide as sticky a nightmare as Polanski or Lynch ever dreamed of making us dream. The movie makes no fucking sense but I was scrubbing myself for hours afterwards.

| . . . 2019-04-03 |

From the moment I heard the Rapture described, I knew with divinely inspired certainty that it had already happened, probably before I was born, and had consisted of sixty or seventy people, none of them ever missed.

And it seems just as silly for us to start worrying about an AI Singularity now, so many years after humanity created something more powerful than humans but competing for the same resources.

mpowell 04.02.19 at 1:23 pm

In particular, the combination of limited liability, principle of shareholder value uber alles as a governing principle of corporate management and corporate personhood – this triumvirate is very much a mistake. I could accept any 2 of the 3, but not all of them together because what they imply together is that corporations should behave in a completely amoral way (corporate ethics as taught in business school is to be exactly unethical as you get away with), that they should be empowered by the courts to pursue these ends with all possible tools at their disposal (eg. political donations) and that liability for crossing legal boundaries is mainly a civil matter for the corporation and rarely reaches the humans behind the decisions. It should be fairly obvious to all that allowing entities to exist that possess all 3 of these properties is purely a creation of state policy and does not flow naturally, even from a principle of natural individual property rights (how do you restrict your liability towards 3rd parties by forming an agreement with just a 2nd party – it doesn’t make sense).

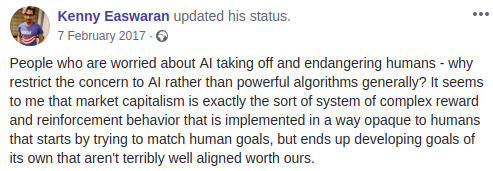

Peli Grietzer finds prior art:

Even apart from his utility to plagiarists, Kenny Easwaran seems like an interesting fellow....

| . . . before . . . | . . . after . . . |

Copyright to contributed work and quoted correspondence remains with the original authors.

Public domain work remains in the public domain.

All other material: Copyright 2018 Ray Davis.