|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|||||

| . . . justifications | |||||

| . . . 2003-06-13 |

"That is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye've time to know."

The proprieter of Everything Burns remarks on a compare-and-contrast opportunity:

I wonder if Don Marquis was familiar with Attar's The Conference of the Birds.Attar's moth searches for understanding and truth; Marquis's moth craves beauty and excitement. The lovers' justifications differ but not their consummation.

Or would a more appropriate word be consumption? In post-archy America, as we noted a few days ago, enlightenment became available only to the purchaser of The Real Thing (just ask the man who owns one), the production of wanting something that badly became industry's chief concern, and now we'd say the moth has bought it.

| . . . 2007-10-21 |

There's a lot of ink spilled over 'meaning' by literary theorists (you noticed that, too?) There isn't much discussion of 'function' (in the relevant sense). But, actually, there is a pretty obvious reason why 'function' would be the preferable point of focus. It's more neutral. It is hardly obvious that every bit of a poem that does something has to mean something. Meter doesn't mean anything. (Not obviously.) But it contributes to the workings of the work. (If you are inclined to insist it 'means', probably all you really mean is that it 'does'. It is important.) "A poem should not mean but be" is somewhat overwrought, in a well-wrought urnish way; but 'a poem should not mean, but do' would be much better.Has any literary theorist really written about 'functions', in this sense?

- John Holbo (with a follow-up on intention and Wordsworth-quoting water sprites)

Analytic philosophers often sound like a blind man describing an elephant by holding the wrong end of a stick several blocks away from the zoo. This is one of those oftens.

When talking about species-wide traits, we need to keep track of teleological scales. One can easily invent (and very rarely find evidence for) evolutionary justifications for play or sexual variability among mammals. But that's not quite the same as asking the function of this tennis ball to the dog who wants it thrown, or of this foot to the cat who's ready for a game of tag, or of this photo of Keanu Reeves to the man gazing so intently. Particulars call for another vocabulary, and art is all about the particulars.

In the broadest sense, art doesn't have a function for homo sapiens — it is a function of homo sapiens. Humans perceive-and-generate patterns in biologically and socially inseparable processes which generally precede application of those patterns. That's what makes the species so adaptable and dangerous. Even in the most rational or practical occupations, we're guided to new utilitarian results by aesthetics. Software engineers, for example, are offended by bad smells and seek a solution that's "Sweet!"

Making of art in the narrower sense may be power display or sexual display, may be motivated by devotion or by boredom. Taking of art touches a wider range of motives, and covers a wider range of materials: more art is experienced than art is made. Clumped with all possible initiators or reactions, an artwork or performance doesn't have a function — it is a function: a social event. Whether a formal affair or strictly clothing-optional, the take-away's largely up to the participant.

As you can probably tell by my emphasized verb switches, I disagree with John Holbo's emendation of Archibald MacLeish. Yes, Ezra Pound and the Italian Futurists thought of their poems as machines which made fascists; yes, Woodie Guthrie thought of his guitar as a machine that killed them. But I've read the ones and heard the other and I didn't explode, and so the original formula's slightly more accurate, if only because it's slightly vaguer.

Still, when you get down to cases, "to be" and "to do" are both components of philosophical propositions. Whereas, as bog scripture teaches, the songness of song springs from their oscillation.

Like function, intentionality tends to be too big a brush wielded in too slapdash a fashion. CGI Wordsworth and miraculous slubmers in the sand sound closer to "performance art" than "poetry," but obviously such aberrations can't accurately be consigned to any existing genre. Nevertheless, I honestly and in natural language predict that insofar as my reaction to them wasn't a nervous breakdown or a religious conversion, it would have to be described as aesthetic: a profound not-obviously-utilitarian awareness of pattern.

Most art is intentionally produced, and, depending on the skill and cultural distance of the artists, many of its effects may be intended. And yes, many people intentionally seek entertainment, instruction, or stimulation. But as with any human endeavor, that doesn't cover the territory. (Did Larry Craig run his fingers under the toilet stall with political intent? Did that action have political consequences?) Acknowledging a possible typo doesn't make "Brightness falls from the air" any less memorable; the Kingsmen's drunken revelation of infinite indefinite desire made a far greater "Louie Louie" than the original cleanly enunciated Chuck Berry ripoff. Happy accident is key to the persistence of art across time, space, and community, and, recontextualized, any tool can become an object of delight or horror. A brick is useful in a wall, or as a doorstop, or as a marker of hostility or affection. But when the form of brick is contemplated with pleasure and awe and nostalgia, by what name may we call it?

|

a poet should not be

A poet should not be mean.

Jordan Davis writes:

Setting aside Holbo's unfortunate reversion to Macleish's formula, I find his distinction between function and meaning (use and mention) useful when discussing the 99 percent of poetry that does not get discussed. To play in prime time, every last function has to show up dressed as meaning.Ben Friedlander on a tangent: 'it's the obscurity of the near-great and almost-good that gets to the heart of things. Which for me is not the bad conscience of tradition (the correction of perceived injustice, which is where tradition and avant-garde clasp hands and sing), but its good conscience, the belief that there are those who "deserve to be forgotten."'

You're right that I sound too dismissive of a valuable insight. It's that damned analytic-philosophy lack of noticing that gets me down. A poem or play does "function" when it works as a poem or play, but how and why it functions isn't shared by all poems or plays, or by all experiences of the poem or play. The Shepheardes Calender and "Biotherm" functioned differently for their contemporaries than for me; even further, the effect of the Calender likely varied between Gabriel Harvey and John Taylor, and "Biotherm" likely did different numbers on Bill Berkson and Robert Lowell. None of this is news to you, of course, but Holbo's formulation doesn't seem to allow room for it.

Jordan again:

To take your point about Holbo -- I appear to have misread him as having spoken about apparent aporias -- I thought he meant that one accustomed to kaleidoscopes might not know how to hold a bicycle.

Beautifully put. And it's just as likely that I misread him, lured into hostile waters by the chance to make that graffiti joke.

But surely 'functions' is a plural enough noun to cover a plurality of cases, no? (How not?)

Way to bum my disputatious high, dude. I've been kneejerking against the vocabulary of John's examples, but, yes, another way to read him (and it's the way Joseph Kugelmass and Bill Benzon read him) puts us more in the same camp.

| . . . 2010-03-09 |

I'm reluctant to call anything a "cultural universal," even something that pretty much decides whether an archaeologist announces the discovery of "culture," but art-making is certainly more universal than the justifications offered for art-making. Which is not to say that art is best when motivated least but merely to confess that, as with other cultural near-universals (marriage, say), any particular motivation won't suffice for the general case. Or even for the particular.

Thus the let-down. Thanks to the Republican furloughs I finally disgorged the "ethical criticism" essay that lodged between brain and trachea for a year and a half, and to quote Lord Bullingdon "I have not received satisfaction." Not that I could receive satisfaction, I know that much by now. Cross-posting to the Valve would've bought me at most a day or two, and appearing in a print organ would've sickened me for months instead of weeks. The least miserable producers I know avoid hangovers by making sure a new project's underway by the time the old one's facing the public. With this dayjob, though, the best I can manage is hair of the dog.

Of course I am obscure; I am not offering myself but my hospitality. Nor do I hawk my hospitality abroad. I give out indications of my willingness to dispense hospitality on a basis that protects my integrity as a host.- Laura Riding, letter to the Times Literary Supplement, March 3 1932,

six years before closing her quaint-curiosity-shoppe-with-New-York-deli-service

Given my mood, I wondered why our beloved metameat didn't flourish das Gift, but upon reflection in someone else's mirror I realized that probably once you've learned German and read Finnegans Wake and a shitload of critical theory you'd get a little tired of that particular false friend, even if no false friend was ever better named.

Or was it? Maybe we can't trust it even that far. A perfect false friend, like a perfect rhyme or perfect pun, should be the product of miraculous chance. Whereas Gift is poison because poison is something given:

[Com. Teut.: OE. ghift str. fem. (recorded only in the sense 'payment for a wife', and in the plural with the sense 'wedding') corresponds to OFris. jeft fem., gift, MDu. gift(e) (Du. gift fem., gift, gift neut., now more commonly gif, poison), OHG. gift fem., gift, poison (MHG., mod.G. gift fem., gift, neut., poison), ON. gift, usually written gipt gift (Sw., Da. -gift in compounds), pl. giptar a wedding, Goth. -gifts in compounds.... The two words 'gift/Gift' in English and German both have the common germanic ancestor geban 'to give'. The rest is separate development through many centuries. The word for 'to poison' used to be 'vergeben'', but it went out of use because of its homophone meaning 'to forgive', and became 'vergiften'.]

It's a gift — a present rather than a presentation — because, like it or not, no matter how loudly we protest our detachment, in a (falsely?) friendly act the giver is there, is implicated. The detective calls his suspects to dismiss them: the victim was poisoned by herself, in a single dose from a table service blunder, or absorbed over a lifetime of serial killing.

Speaking of etymology:

[< Anglo-Norman poisoun, Anglo-Norman and Old French poisun, puisun, Anglo-Norman and Old French, Middle French poison, puison, puisson, Old French poisson, pouson, Middle French poyson (French poison) drink, draught (end of the 11th cent.), poisonous drink (1155), potion, medicinal drink (c1165), poisonous substance (1342) < classical Latin potion-, potio (see POTION n.). Compare Old Occitan, Occitan poison drink, draught (c1150), potion (c1200), poison (early 13th cent.).]

So maybe "Name your poison" isn't such an impressive joke either.

SCOTTIE: "Here, Judy. Drink this straight down, just like medicine."

JUDY: "Why are you doing this? What good will it do?"

SCOTTIE: "I don't know. No good, I guess. I don't know."

you sayin it ought to be the gifted Mr Ripley?

Now there was an artist without regrets!

Jonathan Mayhew kindly writes:

I love that idea that "art-making is certainly more universal than the justifiications for art-making." That encapsulates something I've been trying to get my head around for awhile.

| . . . 2016-12-26 |

I loved my country — my United States, headed by a well-funded and unabashedly ambitious federal government — I loved my country about as much as any halfway sane person could love an unimaginably huge and amorphous institutional abstraction. Which seems only natural since it had rescued, fed, clothed, sheltered, educated, and boosted me and my brother after having rescued and supported our parents.

Of course (being halfway sane) I knew big government was frequently inept, hypocritical, and unjust to the point of murder. But it was also the only rival to and our only defense against the unimaginably huge and amorphous institutional abstractions of big business and big religion, both of which were at least as frequently inept, hypocritical, unjust, and murderous. And where big businesses and big churches could cheat, lie, embezzle, extort, and rape with virtual impunity, big government's pretense of public service left its miscreants nominally (and therefore sometimes actually) susceptible to public inspection and public penalty.

Even while I and my brother were swaddled by socialism, big business and big religion began negotiating an unholy alliance. As of the 1980 election, its success was no longer deniable. But I kept a sullen, resentful faith. My country had absorbed such body blows before and re-righted itself. Weren't the allegiances of evangelical with Jew around Zionism, and evangelical with Catholic around abortion, and church with plutocracy around ignorance inherently unstable?

After the 2000 election, "my country" suddenly looked less like world-as-is and more like a vulnerable blip. 2001 confirmed its vulnerability; the 2004 election guaranteed its loss. Seventy years, approximately the lifespan of the Third Republic.

You know how these things go, though. We understand our loved ones will die, and yet the day finds us unprepared. We understand that gambling is lucrative business; we noticed the casino staff repeatedly extract ever larger winnings and repeatedly produce ever colder decks. And yet when we blankly watch our chips, checks, bonds, mortgage, and IOUs squeegeed dry across the table, it's a shock.

A shock but no surprise.1 No need to waste weeks arguing over how we might have played that last card better. No infallibly winning card was left in this particular game. If we hadn't lost this deal, we would have lost the next one.

At least our razed territory holds plenty of company. Like successful totalitarians of the past, our new leaders didn't let themselves be distracted by the unpopularity of their goals; instead they focused on gaining power by any means at hand, and then guaranteeing continued power by any means at hand. This they interpret as a heroic win against overwhelmingly unfair odds by dint of their superior brilliance and talent.

They've recently attempted to adapt their self-justifications for a wider audience with spins like "saving our country from urban scum" or "defending America against California" or simply "making those fuckers squirm." And of course, as soon as their eminent domain's established they begin demolishing anything in the path of the propaganda superhighway — notably the distasteful slums of reality-based journalism, education, and research. But for a brief while yet, our rulers remain a lunatic fringe who defy majority opinion on almost every policy, and we retain some belief that a democracy should at least vaguely represent its people. History suggests that's common ground enough to push from.

1 Well, one surprise, at least for me. I never anticipated Vladimir Putin as leader of a new Axis. Awfully exceptionalist of me. After "patriotism" lost any connotation of service or sacrifice (even the trivial financial sacrifice of taxes), and frankly selfish plutocrats could reach office without need of political stand-ins, who better to inspire them than the leading exponent of the globalized shakedown state? And whereas Stalin's, Hitler's, and Mussolini's attempts at foreign influence relied on native "thought-leaders" who never quite met spec, now misinformation and propaganda, like every other form of publishing, can bypass the middleman (unless, of course, the middleman is a national firewall), and Russia's greatest export, the bot-troll cyborg, can work from the comfort of home.

Thanks, Bo Diddley.

| . . . 2018-10-28 |

Mojo Hand : An Orphic Tale by J. J. Phillips

1. "Eurydice's victims died of snake-bite, not herself." - Robert Graves

Protagonist "Eunice" is, as we can plainly see, an un-dry Eurydice. And love-object Blacksnake Brown is Orphic because he sets the stately oaks to boogie:

She went to the phonograph there and looked through the stack of records under it. Down at the bottom, dusty and scratched, she found an old 78 recording called “Bakershop Blues” by a man named Blacksnake Brown, accompanied by the Royal Sheiks. She lifted off the classical album, slipped on the 78, then turned the volume up. It started scratching its tune.I want to know if your jelly roll’s fresh, or is it stale, I want to know if your jelly roll’s fresh, or is it stale? Well, woman, I’m going to buy me some jelly roll if I have got to go to jail.

Almost immediately she heard shouts and shrieks from the other room.

“. . . Oh, yeah, get to it. . . . Laura, woman, how long since your husband’s seen you jelly roll?”

“Gertrude, don’t you ask me questions like that. Eh, how long since your husband’s seen you?”

Eunice went back downstairs. Everyone had relaxed. Some women were unbuckling their stockings, others were loosening the belts around their waists. Someone had gotten out brandy and was pouring it into the teacups.

“Give some to the debs,” someone said, “show them what this society really is.”

Just as plainly, though, "Blacksnake" is a snake, with an attested bite. And for all l'amour fou on display, Eunice is only secondarily drawn to her Orpheusnake; first, last, and on the majority of pages in-between, she's after Thrace-Hades:

And even before that she had been drawn to the forbidden dream of those outside the game, for they had been judged and did not care to concern themselves with questioning any stated validity in the postulates. Playing with friends, running up and down the crazily tilted San Francisco streets, they would often wander into the few alleys between houses or stores down by the shipyards. [...] The old buildings were not of equal depth in back, nor were they joined to one another, and there were narrow dark passageways between the buildings. She would worm her way in and out of these, for they were usually empty, though occasionally as she would whip around a corner she would hear voices and would tiptoe up to watch two or three men crouched on the ground, each holding a sack of wine, and shooting dice. She would hide and watch them until the sun went down, marking their actions and words, then tramp home alone whispering to herself in a small voice thick with the sympathy of their wine, “Roll that big eight, sweet Daddy.”

This place which is also a community and a way of living — maybe a good name for that would be habitus? — although nowadays and hereabouts ussens tend to call it an identity. To switch mythological illustrations, what Odysseus craved wasn't retirement on a mountainous Mediterranean island, or reunion with his wife and child, both of whom he's prepared to skewer, but his identity as ruler of Ithaka.

What baits Eunice isn't so much the spell of music but the promise of capture and transportation. Brown's a thin, helpfully color-coded line who can reel her out of flailing air and into Carolina mud, a properly ordained authority to release her family curse (and deliver her into bondage) by way of ceremonial abjuration:

“We-ell, you being fayed and all, I doesn’t want to get in no trouble.”The night was warm and easy, and it came from Eunice as easy as the night. “Man, I’m not fayed.”

He straightened up and squinted. “Well, what the hell. Is you jiving, woman, or what? You sure has me fooled if you isn’t.”

“You mean you dragged me out in the middle of the night into this alley just because you thought I was fayed? That’s the damndest thing I’ve ever heard.” But she knew it was not funny, neither for herself nor for him.

Blacksnake broke in on her thoughts. “Well, baby, if you says so, I believes you. But you sure doesn’t look like it, and you doesn’t even act like it, but you’s OK with me if you really is what you says you is. Here, get youself a good taste on this bottle.”

Eunice took the bottle and drank deeply, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand.

(In many more-or-less timeless ways, Mojo Hand is the first novel of a very young writer. On this point of faith, though, it's specifically an early Sixties novel: that the Real Folk Blues holds power to transmute us into Real Folk.)

2. "Meet me in the bottom, bring my boots and shoes." - Lightnin' HopkinsHaving passed customs inspection, Eunice considers her down-home away from home:

Until this night she had been outside of the cage, but now she had joined them forever.

About twenty-hours later, "the cage" materializes as a two-week stretch in the Wake County jail:

But soon she came to learn that it was easier here. Everything was decided. That gave her mind freedom to wander through intricate paths of frustration.

Jail isn't a detour; it's fully part of Eunice's destination, and afterward she's told "Well, you sure as shit is one of us now." But what sort of freedom is this?

Some people intuit a conflict between "free will" and "reasoned action." (Because reasons would be a cause and causality would be determinism? Because decisions are painful and willful freedom should come warm and easy?) Or, as Eunice reflects later, in a more combative state of mind:

Since her parents had built and waged life within their framework, in order to obvert it fully she, too, had to build or find a counterstructure and exist within it at all costs. The difference lay in that theirs was predicated on a pseudo-rationality whereas the rational was neither integral nor peripheral in hers; she did not consider it at all. To her the excesses of the heart had to be able to run rampant and find their own boundaries, exhausting themselves in plaguing hope.

When the pretensions of consciousness become unbearable, one option is to near-as-damn-it erase them: minimize choices; make decision mimic instinct; hand your reins to received stereotype and transient impulse. Lead the "simple" life of back-chat, rough teasing, subsistence wages, steady buzz, sudden passions, unfathomable conflicts, limitless boredom, and clumsy violence. A way of life accessible to the abject of all races and creeds in this great land, including my own.

All of which Phillips describes with appropriately loving and exasperated care, although she's forced to downshift into abstract poeticisms to traverse the equally essential social glue of sex.

It was completely effortless, with the songs on the jukebox marking time and the clicking pool balls countersounding it all until the sounds merged into one, becoming inaudible. Eunice felt the ease, the lack of rigidity, and relaxed. She would learn to live cautiously and underhandedly so that she might survive. She would learn to wrangle her way on and on to meet each moment, forgetting herself in the next and predestroyed by the certainty of the one to come.

3. "At the center, there is a perilous act" - Robin Blaser

In this pleasant fashion uncounted weeks pass. Long enough for a girl to become pregnant; long enough for whatever internal clock ended Brown's earlier affairs to signal an campaign of escalating abuse which reviewers called mysterious, although it sounded familiar enough to me.

Blacksnake was Eunice's visa into this country. What happens if the visa's revoked? If our primary goal is to stay put and passive, what can we do when stasis becomes untenable?

Shake it, baby, shake it.

Having escaped into this life, Eunice refuses to escape from it:

There was no sense, she knew, in going back to San Francisco, back home to bring a child into a world of people who were too much and only in awe of their own consciousness. They were as rigid and sterile as the buildings that towered above them.

She'll only accept oscillation within the parameters of her hard-won cage. This cul-de-sac expresses itself in three ways:

It seems perfectly natural for the strictly-local efficacy of the occult to appear at a crisis of sustainability, scuffing novelistic realism in favor of keeping it real. The flashback, though, rips the sequence of time and place to more genuinely unsettling effect, and Phillips handles the operation with such disorienting understatement that this otherwise sympathetic reader sutured the sequence wrong-way-round in memory.

It's unsettling because we register the narrative device as both arbitrary and, more deeply, necessary. Being a self-made self-damned Eurydice, Eunice must look back at herself to secure permanent residence. But when the goal is loss of agency, how can action be taken to preserve it?

Instead, we watch her sleepwalk through mysteriously scripted actions twice over.

4. "Black ghost is a picture, & the black ghost is a shadow too." - Lightnin' Hopkins

Immediately after you start reading Mojo Hand, and well before you watch Eunice Prideaux hauled to Wake County jail, you'll learn that J. J. Phillips preceded her there. If you're holding the paperback reissue, its behind-bars author photo will have informed you that both prisoners were light-skinned teenage girls.

If you've listened to much blues in your life, you'll likely know "Mojo Hand" as a signature number of Lightnin' Hopkins. If you've seen photos of Hopkins on any LPs, the figure of "Blacksnake Brown" will seem familiar as well.

Since comparisons have been made inevitable, contrasts are also in order.

Blacksnake Brown is clearly not the Lightnin' Hopkins who'd played Carnegie Hall, frequently visited Berkeley, and lived until 1982. Eunice is jailed for the crime of looking like a besmirched white woman in a black neighborhood at night; Phillips, on the other hand:

In 1962 I was selected to participate in a summer voter registration program in Raleigh, North Carolina, administered by the National Students Association (NSA). [...] Our group, led by Dorothy Dawson (Burlage), wasn't large and the project was active only for that summer; but during the short time that we were in Raleigh, we managed to register over 1,600 African Americans, which, along with other voter registration programs in the state, surely helped pave the way for Obama's 2008 victory in North Carolina. [...] On the spur of the moment I'd taken part in a CORE-sponsored sit-in at the local Howard Johnson's as part of their Freedom Highways program, which took place the year after the Freedom Rides. [...] Our conviction was of course a fait accompli. We were given the choice of paying a modest fine or serving 30 days hard labor in prison; but the objective was to serve the time as prisoners of conscience, and so we did. In deference to my gender, I was sent to the Wake Co. Jail.[...] Thus began a totally captivating 30 days — an immersive intensive in which I got the kind of real-life education I could never have obtained otherwise.

This unexpectedly welcome "captivation" brings us back to Eunice, however, and thence to Eunice's own brush with voter registration programs:

“I don’t want to register.”The boy shifted from one flat foot to another and scratched a festering pimple. “But ma’m, it’s important that you try and better your society. Can’t you see that?”

“No, I can’t.”

He paused a moment, and then proceeded. “Whatever your hesitation stems from, it is not good. It is necessary for us all to work together in obtaining the common goal of equality. It is not only equality in spirit; your living standards must be equal. Environment plays an important factor. You must realize also that it is not only your right but your duty to choose the people you wish to represent you in our government. If you do not vote you have no choice in determining how you will live.”

Eunice chuckled as she remembered Bertha back in the jail. She crinkled her eyes and laughed. “Well, sho is, ain’t it.”

In turn, that "festering pimple" suggests some animus drawn from outside the confines of the book. And in an interview immediately following the book's publication, its author came close to outright disavowal:

"I went to jail to see what it was like. I was in Raleigh on a voter registration drive. Somebody asked for restaurant sit-in volunteers sure to be arrested. I was not for or against the cause, I just wanted to go to jail." [...] Slender, with the long, straight hair, wearing the inevitable trousers, strumming the guitar, she also defies authority in her rush to individual freedom. She lives in steady rebellion against the comfortable — escapist? — atmosphere provided by her parents, both in professional fields and both successful. Her own backhouse, bedroom apartment, her transportation — a Yamaha and a huge, black, 5-year-old Cadillac; her calm acceptance of her right to live as she pleases are all a part of the pattern of the new 1966 young.

(For the record, yes, I'm grateful that no one is likely to find any interview I gave at age 22, or to publish any mug shot of me at age 18.)

Forty-three years later, J. J. Phillips positioned Mojo Hand in a broader context: three separate cross-country loops during an eventful three years which she entered as an nice upper-middle-class girl at an elite Los Angeles Catholic college and left as an expelled, furious, disillusioned, blues-performing fry-cook.

Which of these accounts should we believe? Well, all of them, of course. Here, what interests me more is their shared difference from the story of Eunice.

* * *

The older Phillips summarized Mojo Hand as "a story of one person’s journey from a non-racialized state to the racialized real world, as was happening to me."

As always, her words are carefully chosen. In the course of a sentence which asserts equivalence, she shifts from Eunice's singular, focused journey to something that "was happening to" young Phillips. More blatantly, she tips the balance by contrasting "a state" with "the real world."

Contrariwise, someone might describe my own wavering ascent towards Eunice's-and-Phillips's starting point as "one person's journey from a racialized state" (to wit, Missouri) "to the class-defined real world." I'm not that someone, though. Even at the age of Mojo Hand's writing, when my scabrous androgyny was demonstrably irredeemable, I understood that, should I live long enough, my equally glaring whiteness would bob me upwards like a blob of schmaltz. And indeed, although my patrons and superiors have been repeatedly nonplussed by my choices, none ever denied my right to make them.

Whereas, in America, some brave volunteer or another can always be found to remind you that you're black or female. And in the ordinary language of down-home philosophizin', if you can't escape it, it's real: truth can be argued but reality can only be acknowledged, ignored, or changed. Even if "race" is an unevidenced taxonomy and "racism" is a false ideology, "racism" and "a racialized world" remain real enough to kill — depending on time and place.

As does "class." And, like Phillips in Los Angeles, in San Francisco Eunice was born into a particularly privileged socio-economic class. Even if she'd stayed in San Francisco, she could've chosen to remove herself from that class, most likely temporarily, anticipating the "inevitable pattern of the new 1966 young." But merely by having the choice, she would have become in some sense, in some eyes, a fraud.

The Jim Crow South, however, offered any stray members of the striving class at most the choice of "passing," faudulent by definition. Thus, with the mere purchase of a train ticket, properly propertied individuals could reinvent themselves as powerless nonentities. What racialized Eunice and Phillips was travel to a place in which no non-racialized reality existed. What made that racialization lastingly, inescapably "real" was, for Eunice, a permanent change of residence. For Phillips, back in California, it was recognizing a racism which had previously stayed latent or unnoticed, and which continued to be denied in infuriatingly almost-plausible fashion.

5. "But I didn't know what kind of chariot gonna take me away from here." - Lightnin' Hopkins

Returning to the book's one encounter with progressive politics, after Eunice shuts the door on the pimpled young man, Blacksnake is bemused (not for the first time) by her volitional assumption of a cage in which others were born and bred:

“Oh, shit. Woman, I can’t vote. I been to the penitench. [...] Girl, you got some strange things turning ’round in that head of yours. Why did you come here anyway?”“I don’t know. I just felt like it.”

Eunice sat down on the bed and scratched her head. It was useless to try and find the causes of her being here; she merely was and could never be sure whether it was a true act or a posture of defiance.

Odysseus traveled to reclaim his prior identity. How, though, would someone establish an identity?

By fiat, by fate. With that infallible sixth sense by which we know we were a princess dumped on a bunch of dwarfs, or the infant who was swapped out for a changeling, Eunice knows she's been denied her birthright. Or two birthrights, which Mojo Hand merges:

First, racialization; that is, membership in a race.

Second, the inalienable right and incorrigible drive to make irretrievable mistakes and trigger fatal disasters. In a word, maturity.

Never had she been forced to her knees to beg for the continuation of her existence, nor fight both God and the devil ripping at her soul; never had she been forced to fight to move in the intricate web of scuffle; never had she been forced to fight a woman for the right to a man, nor fought out love with a man. She had never fought for existence; now she would have to.

In well-ordered middle-class mid-century households, these are things parents protected children from, things children couldn't imagine their parents doing. Most of them are part of most adult lives, and once experienced, they're not likely to be forgotten. But depicting them comes easiest when they're assigned to disorderly elements, and a narrative's end is more attended than its torso.

In the novel's introductory parable, a girl who finds the sun (dropped by an old-fashioned Los Angeles pepper tree) is forced by her father to give it up. During her longest residence in Lightnin' Hopkins's Houston neighborhood, Phillips met similar interference: "I especially did not want to suffer the ultimate mortification of being ignominiously carted home by my parents, so I went back to L.A."

If Eunice had been dragged back to San Francisco, that anticlimax would be interpreted as an ironic deflation of a hard-won life. And so, in vengeance for her parents' deracination, Eunice is silently de-parented, and the book instead ends with her both adopting a new mother and waiting to become a new mother.

* * *

The United States between 1962 and 2009 incorporated a whole lot of habitussles, each with its own preferred ways to swing a story. Even as something is done (by us, to us, of us, the passive voice is the voice that rings real) — and certainly afterwards — we're spun round by potential justifications, motives, excuses, bars, blanks.... Whichever we choose, sho is, ain't it.

One year after 22-year-old J. J. Phillips saw Mojo Hand in print, 25-year-old Samuel R. Delany saw his own version of black Orpheus, A Fabulous, Formless Darkness, published as The Einstein Intersection. Neither fiction much resembles Ovid, and where Phillips mythologizes black community, Delany mythologizes queer difference. What the two writers shared was a reach for "mythology" as that which both describes and controls the actions of the mythological hero: a transcript which is a script; a fate justified as fulfillment of fate.

A story to make sense of senselessness and reward of repeated loss.

What Phillips suffered and enjoyed as an indirect, experimental process of frequently unwelcome discovery and retreat, confrontation and compromise, Eunice is able to consciously hunt as a coherent (if not rationally justifiable) destination. The mythic heroine's one necessary act of mythic agency was to decide to enter that story and, mythically, stay there ever after. The oaks rest in place, thoroughly rooted, frozen in their dance.

Lucky oaks.

| . . . 2020-05-03 |

Diagrams are in a degree the accomplices of poetic metaphor. But they are a little less impertinent — it is always possible to seek solace in the mundane plotting of their thick lines — and more faithful: they can prolong themselves into an operation which keeps them from becoming worn out. [...] We could describe this as a technique of allusions.- Figuring Space (Les enjeux du mobile) by Gilles Châtelet

- Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, &c., collected and edited by David Herd, 1776 |

Peli Grietzer and I are separated by nationality, education, career, three decades, and most tastes.1 Our fellowship has been one of productive surprises (rather than, say, productive disputes). And when Peli began connecting machine deep-learning techniques to ambient aesthetic properties like "mood" and "vibe," the most unexpected of the productive surprises represented a commonality:

In relating the input-space points of a set’s manifold to points in the lower dimensional internal space of the manifold, an autoencoder’s model makes the fundamental distinction between phenomena and noumena that turns the input-space points of the manifold into a system’s range of visible states rather than a mere arbitrary set of phenomena.

"A Theory of Vibe" by Peli Grietzer

(If Peli's sentence made absolutely no sense to you — and if you can spare some patience — have no fear; you're still in the right place.)

For two-thirds of my overextended life, I've carried a mnemonic "image" (to keep it short) with me. It manifested as a jerry-built platform from one train of thought to another, satisfactory for its purpose, and then kept satisfying as a reference point — or rather, to maintain its topological integrity, as a FAQ sheet. It guided practice and (if suitably annotated) warned against attractive fallacies. It didn't overpromise or intrude; it answered when called for. Over time it became mundane, self-evident, not worthy of comment. Although I've described its assumptions, its space, its justifications, and its uses, I never did quite feel the need to describe it.

My "image" had emerged from a very different place than Peli's, carrying a different trajectory and twisting out its own series of crumpled linens. What I felt in late 2017 was not so much the shock of recognition as the shudder of recognition with a difference: not a registration error to correct in the next printing so much as a 3-D comic which was missing its glasses. Still, though, recognizably "the same," as if Peli had passed by the smoke and noise of my informal essayism and assembled something resembling the ramshackle contraption which belched them out.

Encounters with an opinion or sentiment held in common always seem worthy of remark, being always scarce on the ground. But some remarks are worthier than others, and greeting years of hard labor with a terse "Oh yes, that old thing," like I was a crate of RED EYE CAPS or something, would be a dickhead move. And so there came upon me the happy thought, "Since Peli has shown his work, it's only fair for me to show mine."

1 Some divergences in taste might be artifacts of our temporal offset: William S. Burroughs and Alain Robbe-Grillet anticipated Kathy Acker and Gauss PDF about as closely as a low-budgeted teenager outside a major cultural center might have managed in the late 1970s, and my side of our most eccentric shared interest, John Cale,2 was firmly established by age nineteen.

2 "Moniefald," in this instance, being more or less synonymous with "Guts."

- "Psyche" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge |

Over the following two-plus years I reluctantly came to realize that "showing my work" may have been an overambitious target: the work that went into that "image" consisted of my life from ages three to twenty-two; the work that's come out of that "image" contains most of my publications and most of what I hope to publish in the future.

That it is useless

Given the evidence of my résumé — a mathematics degree "from a good school," followed by 35 years of software development — you might think it friendlier of me to contribute to Grietzer's research program than to reminisce about my own. Which goes to show you can't trust résumés.

I programmed only to make a living, and every time I've tried to program for any other purpose, no matter how elevated, my soul has flatly refused. "We made a deal," my soul says. "A deal's a deal, man."

Anyway, I don't think the software side of things matters much except as conversation starter or morale booster. Computerized pattern-matching can be useful (and computerized pattern-generation can be entertaining) in their own right, but I'm in the camp who doubts any finite repeatable algorithmic process carries much explanatory power for animal experience, unless as existence disproof that an omnisciently divine watchmaker or omnipotently selfish gene are required.

As for mathematical labor, the work-behind-that-"image" includes the romantic history of my coupling with mathematics: meet-cute, fascinated hostility, assiduous wooing, a few years of cohabitation, and finally an amicable separation. I sometimes think of my "image" as a last snapshot of the old gang gathered round the table before we were split up by the draft and divorces and emigrations.

I haven't spoken to mathematics since 1982. Getting properly reacquainted would take as much effort as our first acquaintance, and, speaking frankly, if I live long enough with enough gumption to repursue any disciplined study, I'd prefer it be French.

I am, however, OK with bullshitting about mathematics, and have very happily been catching up on the past forty years of philosophy-'n'-foundations. Turns out a lot's happened since Hilbert! (Yeats studies, on the other hand, haven't budged.)

That it is trivial

As mentioned above, I never felt a need to describe my "image," much less ask who else had seen it. Once I started looking, the World Wide Concordance easily found some pseudo-progenitors and fellow-travelers. Maybe my exciting personal discovery was something which virtually everyone else on earth already had, unspoken, under their belts, like masturbation, and my reaction to Grietzer's dissertation was a case of "shocked him to find in the outer world a trace of what he had deemed till then a brutish and individual malady of his own mind."

That it is redundant

Also as mentioned above, I've touched or traversed some of this ground before, and came near as dammit to sketching the "image" itself in a summary of development and beliefs which still pleases me by its concision. And here I sketched the transition from positivist analytic philosophy to pragmatic pluralism; there I described the heady combination of Kant and acid; a bit later I wrote all I probably need to write about aptitude and career....

Much of my dithering over this present venture comes down to fear that I'm taking a job which has already been perfectly adequately done, and redoing it as a bloated failure. God knows there are precedents.

That it is

There are two senses of "showing the work" in mathematics. What's typically published is a (proposed) proof, an Arthur-Murray-Dance-Studios diagram which indicates (one hopes) how to step down a stream of discourse from (purportedly) stable stone to stable stone until we've reached our agreed-upon picnic spot.

But closer to the flesh, very different sorts of choreography come into play. For the working mathematician, what impels and shapes the proof is the work of observation, intuition, exploration, and experimentation. For the teacher (depending on the teacher), tutor, or study group, the proof is meaningless without a motivating context and a sense of the mathematical objects being "handled," and those can only be conveyed by implication — by descriptions, metaphors, examples, images, gestures, and applications:

It is true, as you say, that mathematical concepts are defined by relational systems. But it would be an error to identify the items with the relational systems that are used to define them. I can define the triangle in many ways; however, no definition of the triangle is the same as the “item” triangle. There are many ways of defining the real line, but all these definitions define something else, something that is nevertheless distinct from the relations that are used in order to define it, and which is endowed with an identity of its own.We disagree with your statement that the ideal form of knowledge in theoretical mathematics is the theorem (and its proof). What we believe to be true is that the theorem (and its proof) is the ideal form of presentation of mathematics. It is, in our opinion, incorrect to identify the manner of presentation of mathematics with mathematics itself.

- Indiscrete Thoughts by Gian-Carlo Rota

But what are we studying when we are doing mathematics?A possible answer is this: we are studying ideas which can be handled as if they were real things. (P. Davis and R. Hersh call them “mental objects with reproducible properties”).

Each such idea must be rigid enough in order to keep its shape in any context it might be used. At the same time, each such idea must have a rich potential of making connections with other mathematical ideas. When an initial complex of ideas is formed (historically, or pedagogically), connections between them may acquire the status of mathematical objects as well, thus forming the first level of a great hierarchy of abstractions.

At the very base of this hierarchy are mental images of things themselves and ways of manipulating them.

"Mathematical Knowledge: Internal, Social and Cultural Aspects"

by Yu. I. Manin

Similarly, to justify a text a motivated Author is desired; if none is found, religious and literary histories prove that one will be invented. A legislature inscribes laws, but those statutes are meaningless gibble-gabble without politics to justify them and enforcement to materialize them. And hoity-toity structuralist though I am, I confess I gained more from classic philosophy texts after I began reading them as abstract self-portraits.

Something outside the proof, the text, or the statute — and possibly even something outside my cheerfully concise spiritual C.V. — is needed to derive a "real" (that is, "perceived"; that is, "dimensioned") object from what would otherwise be just another segment of a one-dimensional droning continuum — or be even less than that.

To use an image I've used before and will use again, we need to put skin on that game and meat on those bones:

When two proofs prove the same proposition it is possible to imagine circumstances in which the whole surrounding connecting these proofs fell away, so that they stood naked and alone, and there were no cause to say that they had a common point, proved the same proposition.One has only to imagine the proofs without the organism of applications which envelopes and connects the two of them: as it were stark naked. (Like two bones separated from the surrounding manifold context of the organism; in which alone we are accustomed to think of them.)

- Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics by Ludwig Wittgenstein,

third revised edition

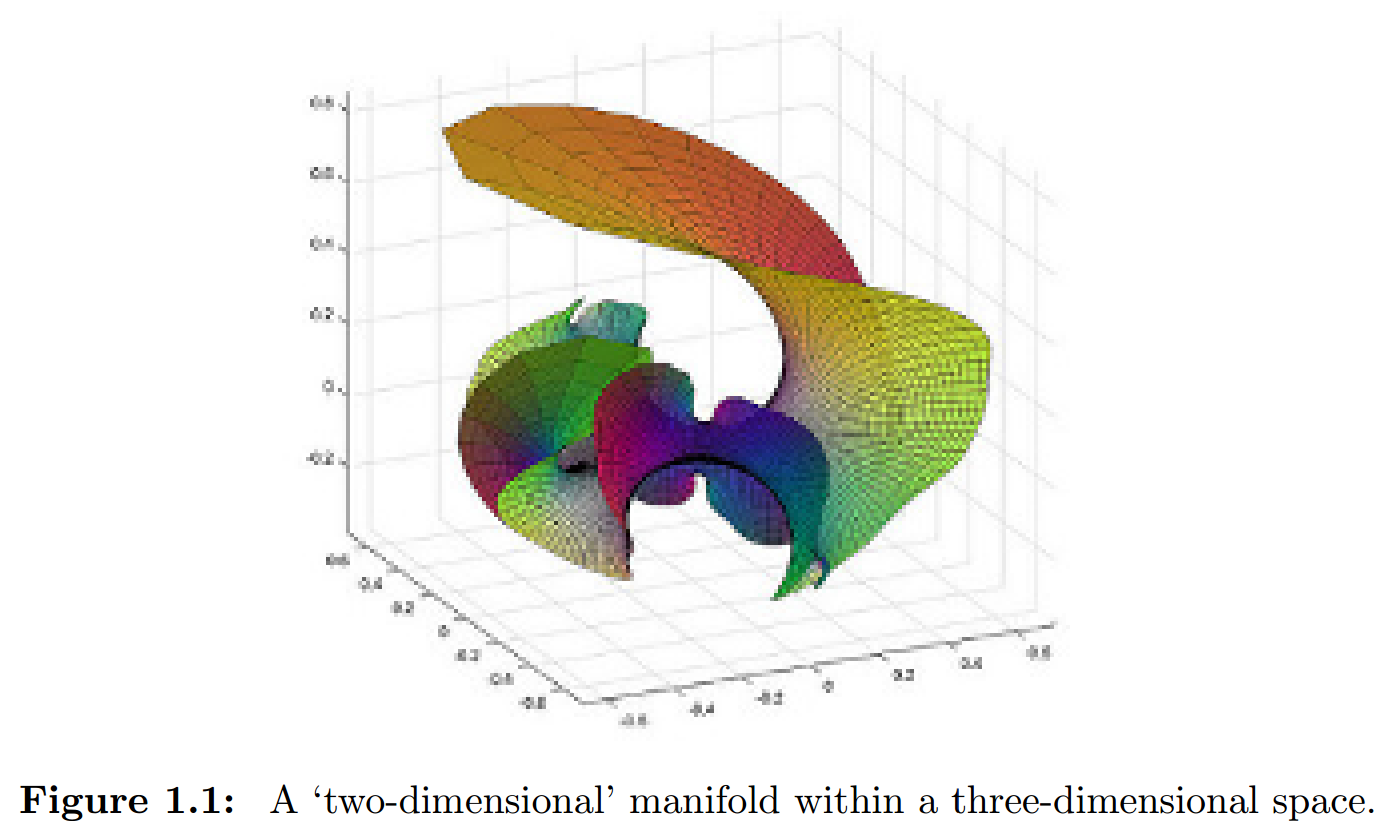

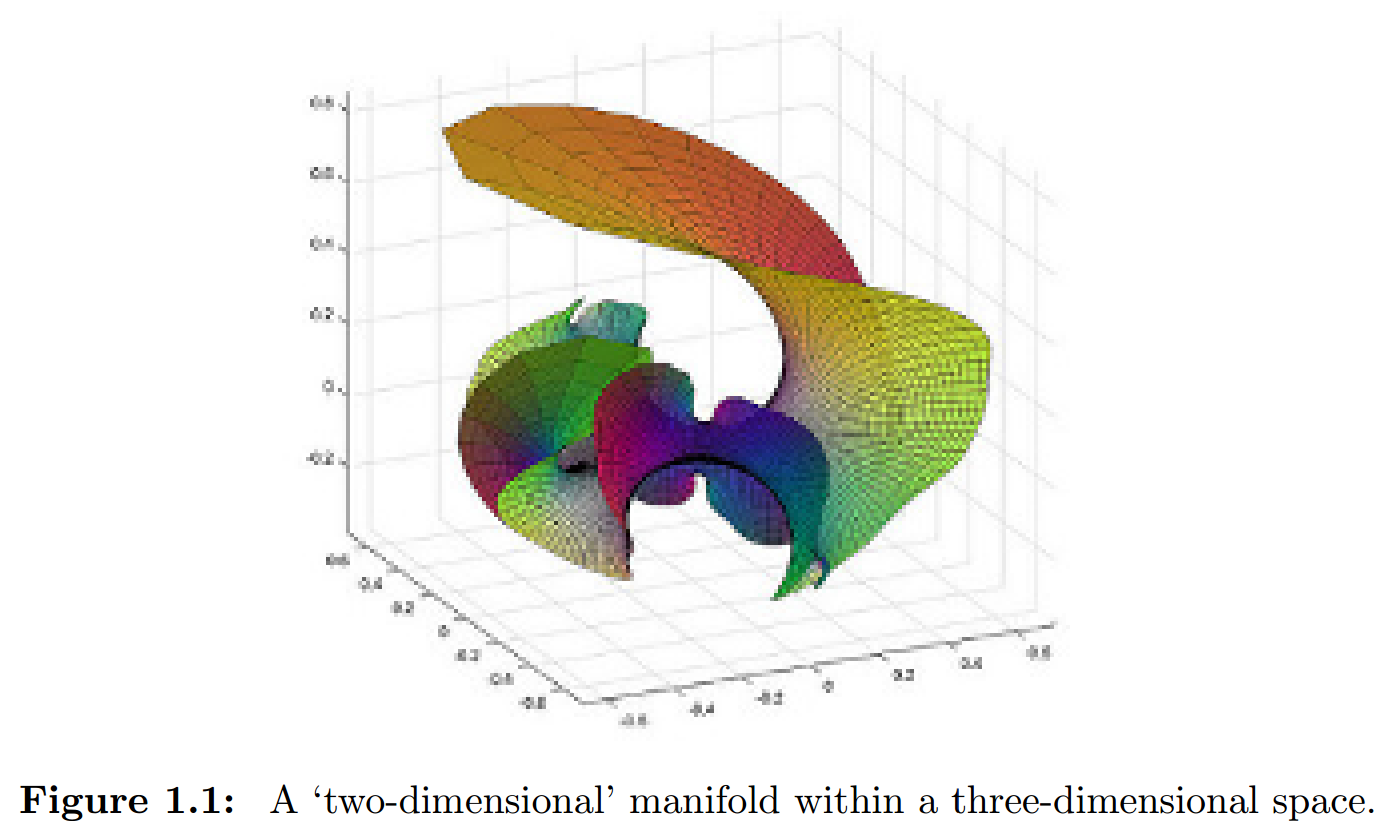

A manifold, in general, refers to any set of points that can be mapped with a coordinate system. [...] In the context of autoencoders, one traditionally uses ‘manifold’ in a more narrow sense, to mean a lower-dimensional submanifold: a shape such that we can determine relative directions on said shape, quite apart from directions relative to the larger space that contains it. From the ‘internal’ point of view—the point of view relative to the manifold—the manifold in the illustration is a two-dimensional space, and every point on the manifold can be specified using two coordinates. From the external point of view—the point of view relative to the three-dimensional space—the manifold in the illustration is a ribbon-like shape curling hither and thither in a three-dimensional space, and every point on the manifold can only be specified using three coordinates.

Ambient Meaning: Mood, Vibe, System by Peli Grietzer

The wolf comes down on the fold; I place a three-fold napkin beside my plate; when we host four guests, we need threefold napkins; when playing poker I either fold early or lose my bankroll.

Given working knowledge of the words many and fold, most usages of "manifold" are fairly easy to decipher:

The apparent exception is mathematics, where the most commonly encountered definition is something along the lines of "a topological space each point of which has a neighborhood homeomorphic to a Euclidean space."

And this isn't just a case of English being led astray, like our settling on computer when the French wisely held out for ordinateur: mathematical-French for manifold is the nearly synonymous variété.

A look at the source which both words were translating clarifies things a bit.

Riemann was more ambitious. He also wanted to generalize Euclidean geometry to handle variable properties other than the familiar height-width-depth of physical space: color or mass, for example. And he wanted to generalize those familiar spatial coordinates to allow for the possibility of other geometries — notably the possibility of a globally non-Euclidean curved physical space, unbounded but finite, similar to the globally non-Euclidean physical surface of the Earth.

To describe those generalizations, Riemann needed words other than "surface" and "space". (As a popularizer of Riemann's ideas told an outraged conservative who accused him of trying "to spread and support the views of the metaphysical school," "The 'manifold' I described in my paper is not a space.") And because his generalization involved a whatsit whose "interior" could be minimally plotted by one or more varying properties, and whose "exterior" could be minimally described by adding one more varying property, he settled on Mannigfaltigkeit. His paper also tries out "n-fold extent" and "n-fold continuum" and "n-ply extended magnitude," but "manifoldness" and "manifold" were less overloaded terms, and so "n-dimensional manifold" won out in the research and textbooks that followed.

Our present-day topological manifold specifies that each point exist in some "neighborhood" of other points, so that the manifold can be treated (locally) like a sub-surface or a sub-space of its own. Riemann's original definition was broader. Because he asked only that the specified things be distinguished by quantifiable properties, his manifoldnesses included collections of widely scattered individuals, no matter how unneighborly they might be:

According as there exists among these specialisations [i.e., instances of the general collection] a continuous path from one to another or not, they form a continuous or discrete manifoldness; the individual specialisations are called in the first case points, in the second case elements, of the manifoldness. Their comparison with regard to quantity is accomplished in the case of discrete magnitudes by counting, in the case of continuous magnitudes by measuring.Although "discrete manifolds" didn't make it into topology, Riemann's rationale for including them still holds interest for myself and Grietzer, I think.

When learning German I had a lot of false-friend interference from Spanish, such that I kept interpreting "mannigfaltig" as "not enough people."

Copyright to contributed work and quoted correspondence remains with the original authors.

Public domain work remains in the public domain.

All other material: Copyright 2024 Ray Davis.