|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|||||

| . . . REAL | |||||

| . . . 1999-06-20 |

Cholly on Software:

"We are a million-year-old beast," he said. "Interfaces will have to mimic how the real world works." One of the ways to do that is to use objects that represent real-world things, like radio dials and on-screen controls for a software application, he said.Radio dials are a million years older than computers? That way lies the QuickTime 4 Player....

| . . . 1999-07-30 |

Twentieth Century Ooze: Like any smart science fiction writer, Bernard Wolfe, author of cult-novel Limbo ("I think it is a masterpiece" -- David Pringle, Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels), knew that he was describing the present, not the future: "I am writing... in the guise of 1990 because it would take decades for a year like 1950 to be milked of its implications." Mind-control was a global preoccupation in the novel's birthyear, and so Limbo plays as many variations on lobotomy as Philip K. Dick on hallucinogenic drugs or Rudy Rucker on fatuous preening.

Equally accurate but not quite so self-aware is Wolfe's depiction of sexual attitudes among the educated and heterosexual. In a central episode of the book, the hero undergoes the indignity of having a women straddle him ("only a frigid woman would have to make such an issue of the top billing.... the most difficult of positions, a man-deposing position which for most women would exclude the possibility of any real orgasm at all -- a full vaginal one, not a pale clitoridean substitute") followed by the further indignity of her autonomous movement ("he did not relish that part of him which could be aroused in this passive way.... beholden to no man for her triumph, involved with her partner only insofar as she had momentarily borrowed him as a necessary prop....") and, worst of all, mutual satisfaction ("The most frustrating and humiliating erotic moment of his life, he thought with a grimace.").

And what a waste of time! "You had a full experience, sure, but it took you a hell of a long time to arrive at it: well over thirty minutes, I'd say, whereas the average normal coitus lasts for only a few minutes. And like all women who achieve satisfaction only with great difficulty, and only under special aggressive circumstances and only after prolonged tension and anxiety, you were determined to be the pace-setter. That's quite characteristic of frigid women too -- the men's mechanism must be only a passive reflex of theirs. You'll find this hard to believe, but the normal state of affairs is quite the other way around.... With a kind of warm melting you don't know anything about."

To prove his point, he rapes her. In the proper missionary position.

But she even manages to screw that up! "It was not, although it had started out to be, the genuine full reaction of the wholly yielding, wholly warm woman -- she, or her ornery unconscious, had executed a diversion to defeat him at the last moment, at the price of her own full satisfaction."

If all of the women he meets are either openly frigid or covertly frigid, how can he talk so confidently about "normal" women? Ah, the age-old problem for male pontificators, solved in the age-old way with the invention of a fantasy: the perfectly yielding Gauguinesque island girl, Ooda. Good old puddin'-headed Ooda. Nothing like his first wife....

Much more straightforwardly instructive than work by such old prevaricators as Norman Mailer, Limbo is highly recommended to postfeminists, Lacanians, and the nostalgic.

And only a quarter-century after Limbo's publication, noted heterosexual intellectual male Woody Allen was ready to debunk the two orgasm theory, although, naturally, he had it mouthed by a silly-billy blonde bimbo rather than by a heterosexual intellectual male.

| . . . 1999-09-02 |

In production: The recent news that Christopher Walken will star in a musical version of James Joyce's "The Dead" made me thankful once again that Dubliners hasn't gotten the Andrew Lloyd Webber treatment.

Picture the second act curtain: Bernadette Peters in old(er)-age makeup bellowing "I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls" to a lambada beat while the Titanic hoists gigantic sail for Buenos Ayres....

On the other hand, Joyce's much-expressed love of cornball music would give Randy Newman a shot at his best Disney score yet, albeit at the cost of turning all the characters into mice:

Conley ran his tongue swiftly along his twitching pink nose.-- O, the real cheese, you know....

| . . . 1999-09-09 |

The prole thrillers which came closest to the jokey splatter of neo-noir weren't from Mickey Spillane but from Chester Himes. I recently read the second volume of Himes's autobiography, which, amidst hundreds of pages of complaints about girlfriends, royalties, and his Volkswagen, revealed just how liberating Himes found the hard-boiled genre after a dozen years of working the Richard-Wright-defined mainstream:

I would sit in my room and become hysterical thinking about the wild, incredible story I was writing. But it was only for the French, I thought, and they would believe anything about Americans, black or white, if it was bad enough. And I thought I was writing realism. It never occurred to me that I was writing absurdity. Realism and absurdity are so similar in the lives of American blacks one can not tell the difference..... I was writing some strange shit. Some time before, I didn't know when, my mind had rejected all reality as I had known it and I had begun to see the world as a cesspool of buffoonery. Even the violence was funny.... If I could just get the handle to joke. And I had got the handle, by some miracle.

I didn't really know what it was like to be a citizen of Harlem; I had never worked there, raised children there, been hungry, sick or poor there. I had been as much of a tourist as a white man from downtown changing his luck. The only thing that kept me from being a black racist was I loved black people, felt sorry for them, which meant I was sorry for myself. The Harlem of my books was never meant to be real; I never called it real; I just wanted to take it away from the white man if only in my books.

| . . . 1999-10-12 |

Chip Morningstar's Postmodern Adventure (via Cardhouse) is the best geeks-look-at-gobbledegook piece I've seen. But the peculiarities of the contemporary American academy have confused his take on the French origins of poststructuralist style: Derrida, for example, is a professional philosopher, not a critic; his work is interesting as philosophy (and, depending on one's taste, as literature), not as lit-crit. And Morningstar doesn't go far enough in his paralleling of the two communities. If I may demonstrate:

| Academic Post-Structuralists | Computer Programmers | |

| Supposed Goal | Improved understanding of artifacts | Improved efficiency of tasks |

| Actual Goal | Career in kinship group | Career in kinship group |

| Problem-Solving Approach | Jargon-constricted language with unnatural syntax | Jargon-constricted language with unnatural syntax |

| Water-Muddying Foreign Disciplines of Record | Philosophy, psychology | Engineering, mathematics |

| Real Water-Muddiers | Obsessive-compulsive egocentricity | Obsessive-compulsive egocentricity |

| Destructive Kinship Rite | Crossreferencing | Long hours |

| Result of Kinship Rite | Smugness / paranoia about obviously unfinished work | Smugness / paranoia about obviously unfinished work |

| Most Hilariously Unfulfilled Promise | Social justice | Ease of use |

| . . . 1999-11-02 |

My fellow movie loons should do their utmost to preserve Turner Classic Movies' upcoming broadcasts of Howard Hawks's The Big Sky. Which is to say, Howard Hawks's The Big Sky. Here's how Hawks told the story:

It opened in Chicago at a very good theater and was doing fabulous business. They asked me to fly back there and we looked out the hotel window to the theater and there were lines that went clear around the corner and down the street. They said, "We wanted you to see this because if you'll take twenty minutes out of it, we can get another show in." And I said, "You take twenty minutes out and I don't think you'll have a show. You can't do it and have the same picture." But they had the right to cut it and they did. Within a week, those lines dropped to nothing. The picture did, too.... The scenes that made the relationships good were gone, so all of a sudden you were hit with this strange relationship and you didn't know where it came from.As befitted his producer-director position, Hawks tended to be a bit of a blame-passer, so I had my private doubts about just how much he could have overcome the central miscasting of Kirk Douglas, always more convincing as slinking creep than as virile life-force. But that was before, without any fanfare whatsoever, TCM's wonderful researchers found a copy of Hawks's original cut and used it to add 17 minutes to the film.

Non-fellow-movie-loons should be aware that this isn't so much a restoration as it is a series of insertions: the footage from the rare print is in noticeably unpristine shape, and it repeats some voice-over narration that was re-recorded for the trimmed version. But Hawks was a master of rhythm, and with the original rhythm of the storytelling back in place, the movie is transformed. What was a muddled collection of wannabe-big scenes is now an organically structured oral history shading into folktale. What was an artificially inserted romance turns real and necessary. And the laughably tough heroes gain vulnerable Hawksian flesh: now it seems to take months for these guys to heal.

| . . . 1999-11-14 |

Big business monkeys: A story ripped from sixty-five-years-later's headlines, High Pressure remains the best fictional treatment of Internet startups, taking us from moronic vision statement through publicity-inflated stock prices to a happily sold-out ending in only 72 minutes of overtime.

Although mostly sticking to sober reportage, the movie does offer one innovative management idea: unlike most Silicon Valley companies, High Pressure's is careful to restrict its blowhard chief executive to strictly figurehead status, attracting favorable attention from venture capitalists and the press while not interfering with the progress of real work. Why aren't they teaching this at Stanford?

| . . . 1999-12-08 |

For years now I've wondered (in my usual "what, me do the research myself?" way) why so many people wrote about the Brothers Grimm and so few wrote about the people (mostly women) who actually came up with their stories.

For one thing, there's the matter of credit going where it's due; after all, the Grimms weren't working all that long ago. For another, there's all the attention paid to what fairy tales supposedly tell us about childhood -- when, logically speaking, they should tell us much more about the preoccupations of the women ghostwriters and the assumptions of the credited folklorists (and, later, the marketing acumen of the Disney corporation).

And so I found Thomas O’Neill's Grimm story surprisingly satisfying. You have to shove past the National Geographic house style to get to them, but it includes some speculation on the influence of the informants' working lives and some real names:

| . . . 1999-12-17 |

The lights are strung up, Cholly's strung out, and the Club's finally got the true holiday merchandising spirit prancin' and dancin' and donnin' and blitzin' in The Hotsy Totsy Discount Warehouse Outlet:

|

|

|

| . . . 1999-12-31 |

Nothing sums up the 1990s better for me than the remarkable document that follows. (For best results, read aloud.)

Here's hoping that the next decade is less large and more pleasant: cheers! -- Cholly

Finally -- a brand-new right-between-the-eyes, slam dunk men's magazine that lays it all on the table. And shows you how to live smart, live stylishly and live large. Introducing P.O.V. -- the bold new men's magazine for you and your very best friends. Rolling the dice. Taking chances. Scoring big. And playing it smart in-between.

Dear Friend:

Tired of all those super-slick "men's magazines" that show you toys you can't afford, trips you can't take, and clothes you wouldn't be caught dead in?

Wish you could grab the publishers by the lapels and scream, "Get real!!!"

Well here's good news! Because here's P.O.V. Our kind of magazine. From our point of view. Yours and mine. Real guys. Who want real answers.

The first men's magazine to see things the way you do. Speak your language. And give you what you want to know more about. Careers. Cash. And making your weekends count.

P.O.V. is about taking control. Thinking big. Making some cash. Being your own boss. Starting a business. Investing wisely. Staying in shape. Traveling cheap. Getting it right. And getting it often. Living large. And living an active life.

P.O.V. shows you how to do it. Because it's written by guys who are doing it right now.

It looks different. Feels different. And has a fresh new attitude. Irreverent. Witty. Stylish. With a great sense of humor. And a big set of -- well, you know.

P.O.V. lays it all on the table...

It's interviews with people who matter Like Dave Matthews of the Dave Matthews Band. Matthew Perry of Friends. Seinfeld's Michael Richards. MTV's Idalis. ESPN's Dick Vitale. Governor John Engler. All in P.O.V.

It's sex like you've never had it before What I mean is, our sex columnn is different. We pose the same question to our male guy and our female gal. He-said-she-said kinda thing. We've asked...Does size matter? Who wants it more? What's your biggest turn-on? Is it possible to have too much? (What?!)

Just bring up (sorry) a few of these eyebrow raisers next time you're on the Net, and see where things go from there.

Plus we delve into music worth hearing. Movies worth seeing. Books you ought to know about. And other things that matter. All in P.O.V. (You're likin' this already, aren't you?)

If you're ready for a new kind of magazine that packs a big wallop and hits you where you live...

Then welcome to P.O.V.! I'm anxious to hear your opinion of your FREE Charter Issue! Act now! And I'll send it pronto!

Sincerely,

Drew Massey

| . . . 2000-01-05 |

The other interesting thing about BBC America is its occasional presentation of "One Man and His Dog" (or, as we prefer to call it in our more enlightened household, "Person with Puppie"). (Link via Juliet Clark) Most Americans probably only know of sheepdog competitions through their parody in Babe, but the real thing is infinitely better -- if you like to watch genuinely happy doggies more than computer-manipulated pigs, that is (and if you don't, why am I bothering to talk to you?), because nothing could be happier than a working dog working. "Lassie" is soft-core at its most deceitfully mawkish and showdog shows are Victoria's Secret catalogs, but "Person with Puppie" is real hard-core dog-lover porn, hurrah!

So, as with "Iron Chef", we get a TV show premise so sure-fire that it probably doesn't even need a match. But that's not all we get! We also get the heartbreakingly damp beauty of sheep-country scenery, a color commentator who makes John Madden look like George Bush, and shepherds who're usually unflaggingly patient, wildly accented, and sexier than Harvey Keitel by a long shot and a close up both.

| . . . 2000-01-11 |

It's nice to find out that Lynda Barry is a fellow member of the Class of Jimmy Carter. During that high tide of financial aid, my fancy-pants liberal arts college was pretty much as affordable as Northwest Missouri State. And though the shock of those first encounters with the upper crusts was painful, it was also way too central and complicated an experience to regret.

Not that anyone was waiting for my opinion to resolve its ambiguity. By the time I graduated, a few years of Reaganomics had ensured a shock-free campus whose incoming class seemed split between rich kids who wanted to be the heroes in Animal House and rich kids who wanted to be the bad guys in Animal House.

Which is how it should be, says Nicholas Lemann, who I quote:

I'm more with the American people on this.mostly 'cause of the patrician tang of that old speakeasy password "the American people": Nicholas Lemann, the American people; the American people, Nicholas Lemann... Nicholas Lemann is the one with the suit.

Lemann is appalled that scholarship kids, in contrast to preppies, are so often intent on selfish ends. But if we drop that nasty pseudo-egalitarian testing crap, how do we decide who should be allowed four years of private school? Simple: we only pick those who have already successfully completed four years of private school!

You should make judgments about people not prospectively based on a score but in real time based on how well they perform the activity for which they are being selected.Which makes sense as long as you never want anyone to learn anything new. And Plato says you can't really learn anything new anyway, so there you go.

| . . . 2000-02-09 |

Not Going to See the Movie Comment: I was too young to deal with Mansfield Park the first time I read it, and I can't picture a living commercial movie director who isn't. Maybe if Kubrick had been interested in women, he could've managed it instead of Barry Lyndon. Maybe the Hitchcock of Vertigo and The Wrong Man could've, if he didn't mind having another flop.

But probably it's best left to an uncommercial experimenter like Valeria Sarmiento, 'cause it's never going to be a popular story: it's too unpleasant to seem charming and too pleasant to seem important. And unless you maintain that sour-and-sweet balance between the character of poor fostered-cousin Fanny Price and the voice of Jane Austen, you might as well throw the book back onto the Unfilmable shelf.

In fact, they're her only real supporters for most of the book; they want nothing less than to be her Fairy Godmother and Prince Charming. But a Cinderella whose self-worth is based on moral rectitude won't have truck with black magic no matter how much bippity-boppity-boo is sprinkled on it. And, this being Cinderella's story, the villains are not only spurned but punished for their worldly, witty, forgiving ways.

There's no sense of hypocrisy in all this, mind. Instead, we're led to posit an otherwise undetectable particle distinct from both the protagonist and the narrative voice: the human being that produced them.

While Fanny suffered in the attic of her foster mansion,

it seemed as if to be at home again would heal every pain that had since grown out of the separation. To be in the centre of such a circle, loved by so many, and more loved by all than she had ever been before; to feel affection without fear or restraint; to feel herself the equal of those who surrounded her....In the most harrowing sequence of the novel, our little Lisa Simpson gets stuck with her wish:

It was the abode of noise, disorder, and impropriety. Nobody was in their right place, nothing was done as it ought to be.Insofar as a family circle exists, its centre turns out to be a newspaper, since a TV would've been anachronistic. But mostly the circle is untraceable under the dirt, and the snobbish side of Fanny quickly and definitively wins out over the sentimental side. After all, snobbery is fed by a constant flood of evidence, while sentiment is fed only with infrequent scraps.

Mansfield Park is well-nigh unique (some of Hammett's work aside) in celebrating the narrowing of horizons. Far from incorporating new friends and experiences, Mansfield Park ends with the expulsion or death of virtually all characters other than Fanny and her mate. But "my Fanny, indeed, at this very time, I have the satisfaction of knowing, must have been happy in spite of everything." She didn't mind her chains after all. She just didn't want them yanked.

.... to complete the picture of good, the acquisition of Mansfield living, by the death of Dr. Grant [Fanny's father-in-law], occurred just after they had been married long enough to begin to want an increase of income, and feel their distance from the paternal abode an inconvenience.Once the titular estate is completely emptied, the two religious caterpillars are able to cocoon happily ever after.

And that's OK by me, since I like Fanny almost as much as the villains and the narrator do. But then I wouldn't be all that popular in movie theaters either....

2015-06-09 : Regarding the "narrowing of horizons," Josh Lukin adds a contender:

You'd be surprised at how many people think We Have Always Lived in the Castle ends happily (Although I guess Constance's horizons aren't broad at the start, however much she wants to imagine that they are).And, following up:

I had in mind the feminist readings that say, Yay, productive community among women, for which one has to pretend that Constance likes where she ends up as much as does her sister, rather than having to relinquish all her hopes and become a '60s homemaker, as it were. Reflecting on it, I guess it's no surprise that some readers trust Merricat so much that they miss that part.

| . . . 2000-03-02 |

The Bright Elusive Button Fly of Love

From PRODIGAL GENIUS: The Life of Nikola Tesla by John J. O'Neill:

"I have been feeding pigeons, thousands of them, for years; thousands of them, for who can tell --Juliet Clark: "Do you think Tesla knew how a man loves a woman?""But there was one pigeon, a beautiful bird, pure white with light gray tips on its wings; that one was different. It was a female. I would know that pigeon anywhere.

"No matter where I was that pigeon would find me; when I wanted her I had only to wish and call her and she would come flying to me. She understood me and I understood her.

"I loved that pigeon.

"Yes," he replied to an unasked question. "Yes, I loved that pigeon, I loved her as a man loves a woman, and she loved me. When she was ill I knew, and understood; she came to my room and I stayed beside her for days. I nursed her back to health. That pigeon was the joy of my life. If she needed me, nothing else mattered. As long as I had her, there was a purpose in my life.

"Then one night as I was lying in my bed in the dark, solving problems, as usual, she flew in through the open window and stood on my desk. I knew she wanted me; she wanted to tell me something important so I got up and went to her.

"As I looked at her I knew she wanted to tell me -- she was dying. And then, as I got her message, there came a light from her eyes -- powerful beams of light.

"Yes," he continued, again answering an unasked question, "it was a real light, a powerful, dazzling, blinding light, a light more intense than I had ever produced by the most powerful lamps in my laboratory.

"When that pigeon died, something went out of my life. Up to that time I knew with a certainty that I would complete my work, no matter how ambitious my program, but when that something went out of my life I knew my life's work was finished."

| . . . 2000-03-09 |

Everything I need to know about American politics I learned from Henry Adams.

His History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison diagrams the first of our country's Jimmy-Carter-to-Ronald-Reagan drunken staggers with "How Things Don't Work" clarity. His novels, Education, and letters provide a lifetime's course on the place of the intellectual in American government (somewhere behind the croquet mallets in the back of the garage).

And so, in big election years, I turn to Henry Adams for guidance:

"Everything here creaks and groans like a heavy old Dutch man-of-war in bad weather. Congress is floundering over necessary business and inventing all kinds of excuses for steering nowhere. The single great and controlling political fact is our national prosperity which is stupendous, and covers all waste of force....I have noticed a general law that our entire political system breaks down in the winter before a general election. The moment a course is adopted, the terrors begin and the votes fall off. The politicians are fleas; they jump just because they are made that way....

The Democrats are clutching frantically for an issue. The Republicans are crawling on all fours for votes. [For Year 2000 conditions, reverse the parties.] The Germans rule the Republicans; the Irish rule the Democrats; and money is the ruler of us all. I see no public measure to care about. There is no real difference of opinion. But they have to talk."

| . . . 2000-03-10 |

Overheard in the Castro / Noe Valley overlap:

"...get home to the kids.""Oh.... Are they real kids or are they dogs?"

| . . . 2000-03-17 |

Elements of Film Style:

"Critics are inclined to belittle them and call them cheap. But they don't seem to sense the idea that life is made up largely of melodrama. The most grotesque situations rise every day in life.... And yet when these true to life situations are transferred to the screen, they are sometimes laughed down because they are 'melodrama.' |

|

Those of us who have attended fiction workshops may recognize this as the flip side of the common warning against overly dramatic plot points whose only defense is "But that's how it really happened!" Some such warning is needed, as those of us who have read manuscripts in fiction workshops can testify, but when overapplied leads to the numbly unmoving body of cliché called "literature" by its practitioners and "MFA crap" by everyone else.

And then we end up relying on the unguiltily mendacious genre of the memoir to get our melodrama fix.

Not a pretty sight. Not compared to a Borzage movie, anyway.

Our memories and self-images are formed of stories. And so it's inevitable that we're particularly drawn to the most obviously story-like (i.e., melodramatic) incidents that crop up in our "real life," and that we strive to make the incidents that seem important to us more story-like.

But when we put ourselves to the job of story-telling rather than the job of real life, we're operating in a different context. In real life, it's excitingly unusual for story-like forms to appear. In story-telling, it's expected; you don't get extra credit for producing a story that does nothing but sound like a story -- that's the bare minimum that you promised when entering the fray.

Borzage (along with most of the other narrative artists I love) shows by example that melodrama is not a guarantee of success, to be clung to; nor a guarantee of failure, to be shunned. Melodrama is an added responsibility, to be taken on and dealt with, to be rewarded and punished. Melodrama executed with courage, wit, observation, and beauty will always carry more weight than work that avoids "grotesque situations."

And it'll also always run the risk of being laughed down.

| . . . 2000-04-02 |

"The gentleman reader cannot fairly be expected to work up a professional interest in a woman who picked up threads and ate them." -- newspaper review of The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes ColemanWell, that's obviously changed. The Shutter of Snow must be the twentieth-or-so "woman goes crazy but eventually gets out of the institution" novel I've read. Which is the kind of number I'd a priori only expect from plotlines like "boy gets girl" or "detective solves mystery."

Let's take it for granted that insanity is interesting. Why the gender gap, then? Why the Padded Ceiling?

One obvious reason is that well-educated women are (still) more likely to be institutionalized than well-educated men. As the old formula goes, women are institutionalized, poor men are jailed, and the rest of us pretty much do what we want.

Another (not necessarily unrelated) reason is that story-consumers and story-makers prefer that protagonists who show weakness be female. And going crazy and recovering are both pretty obvious signs of weakness. When I was trying to write fiction about loonies I've known, most of whom have been male, I felt immense internal pressure to turn them into female characters instead. (Like, try imagining Repulsion with a male protagonist. No, I mean it: try. It's good for you.) The standard storylines tell us that women go into institutions because they go crazy and men go into institutions because they're rebels. Women get better and men keep insisting they were right. (Sylvia Plath vs. Ezra Pound; The Shutter of Snow vs. One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest....) Men-going-under stories tend to be about addiction rather than madness: appetite, not fragility.

But there's another reason for the twentieth century having produced so many of these stories: the number of untold and unrecoverable stories left over from the nineteenth.

"My mom says that when she was growing up in New Zealand in the Fifties, there were three career options for women: emigrate, become an airline stewardess, or go crazy." -- Juliet ClarkTake out emigration and airlines, and you're left with the options for the nineteenth-century Anglo-American upper class. In feminist-backlash post-abolitionist late-1800s America, good girls had achieved Stendhal's proto-feminist dream: women were being educated but only so that they might be fitter companions to educated men. In the post-feminist era, it wouldn't be tasteful to try to be anything else. A nice New England woman in politics? Laughable. In literature? In art? Etc.

"Any woman learning Greek must buy fashionable dresses." -- Henry Adams regarding his wife, Clover Hooper AdamsThe Civil War, with its bandage-making and fund-raising, was the high water mark of usefulness for the Adams/James generation of American women. Afterwards, if you were lucky, you could have children till you died in childbirth. If you weren't lucky, you either (like Alice James) shrunk into a mockingly dense point of invalidism or you found yourself over an abyss.

"We are working very hard, but it is all for ourselves." -- Clover Hooper AdamsAn abyss-swimming man might clutch for a job; a woman could only be headed for the bin. And in the nineteenth century they tended not to come back out.

"I shall proclaim that any one who spends her life as an appendage to five cushions and three shawls is justified in committing the sloppiest kind of suicide at a moment's notice." -- Alice JamesAs a girl, Clover Hooper swapped dark comparisons of the hospitals that swallowed up her female relatives and friends:

"I wish it might have been Worcester instead of Somerville which is such a smelly hideous place."As an adult, after almost a year of depression, she poisoned herself with her own photo-developing chemicals rather than face institutionalization.

"Ellen I'm not real -- Oh make me real -- you are all of you real!" -- Clover Hooper Adams to her sister, a few months before her death

| . . . 2000-05-09 |

100 Super Movies au maximum: Swordsman II

I never understood the Star Wars thing until I saw Swordsman II. I still don't understand how it applied to Star Wars, but at least now I understand the thing.

|

And the Peter Travers Big Blurb effect: I laughed! I cried! I jumped! I fell! I felt that extremely pleasant sense of complete exhaustion that one usually feels after swimming or dancing all night or doing you-know!

How's the magic worked, besides by swinging great movie stars around on wires?

Pacing, for one thing. We plunge in medias Cuisinart and never pause for exposition, which means the movie not only rewards re-viewing but insists on it. Not to say that we're always moving fast -- a 10-yard-dash isn't the same as pacing -- but there's always something going on. No, multiple things. Big ones, too. Like we're seeing life as we'd see it if we weren't blinkered, which is the sense of revelation that movies were born to deliver.

Like there's the traditional sequence of getting locked in a dungeon and rescuing the poor old tortured guy and escaping, but rather than waiting another couple of scenes before showing the ambiguous ethics of this particular poor old tortured guy we get a nightmarish demonstration during the escape itself: Yoda turns into Darth Vader before our very eyes. And we're still stuck with rescuing the poor old tortured SOB even though now we know those battleship-anchoring chains weren't overkill.

Swordsman II ratchets along a matrix of interlocking conflicting motives: love vs. loyalty vs. ambition vs. revenge; snakes vs. scorpions; Highlands vs. Holland....

|

|

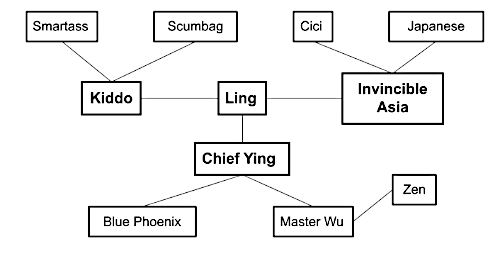

Whatever forces created Swordsman II realized that you build a movie's intensity not just by arranging scenes in order of their budget, but by raising the emotional stakes. As one of Swordsman Ling's idiotic poems might phrase it, "Life is entanglement. Entanglement creates suffering. Where then is peace to be found?" Invincible Asia's weapons of choice are needle and thread, and entanglements build up steadily scene by scene into a narrative woven so tightly that it seems unbreakable.

Throwing superpowers behind these at-odds good intentions only accelerates the dismal outcomes. That's a moral that Watchmen muddied due to the irreconcibility of moral conflict with the American superhero tradition, but pessimism is a firmly established mood in Chinese escapism -- imaginary gardens with real politik. It's not power that corrupts: it's purpose. There's no dependable dichotomy of "dark" and "light" force, just cross purposes.

So, following the same firmly established mood, the most purposeless of all the characters, the lazy alcoholic womanizer Ling, who lacks even spiritual ambition, inevitably becomes the object of all desire. We can only hope he finds a less masochistic form of Zen in Japan.... As for the rest of us, we're doomed to another cycle of strife and attachment and suffering. Which is to say, let's watch Swordsman II again!

Postscript, 2011-02-05 - We just watched the most recently available DVD, idiotically credited as "Jet Li's Swordsman 2" but otherwise acceptable. Sadly for us old-timers, the original HK subtitles were replaced. Notable changes include:

- Self-mortifying "Zen" is now self-mortifying "Heung".

- "Hero of Heroes" lost all its former titles in favor of something about waves-and-shores, leading to loss of the musical question "May I ask who is the Hero of Heroes?"

- Loss of the immortal line "Kiddo has three heads!"

| . . . 2000-05-11 |

pundit.org

"Encapsulation, Inheritance and the Platypus effect" is a not-bad little keep-it-honest rant for programmers, but the author mistakingly blames object-oriented languages for some foundational trip-me-ups of software engineering. He almost says it himself: Object-oriented techniques aren't so much useful because they map the real world, as because they map how software engineers think. I've always done my top-level design in what was later called a "object-oriented" way. Using an object-oriented language just shortens the trip from design to implementation. The better the language, the shorter the trip, which is why I still miss ScriptX.

Having said that, it's always good to be reminded of our besetting sins as software engineers and humans. Premature overgeneralization, for example, which is just Our Gang's variation of humanity-at-large's besetting sin, rushing into categorization. We receive so many internal and external rewards for generalizing and categorizing that we tend to anticipate categories long before we've had enough experience to justify them, and then feel forced to defend our itty-bitty-witties against all enemies (i.e., facts). Thus, our anticipations lead us to ignore the evidence of the real world (and, admittedly, reap the often sizable rewards of ignorance) rather than preparing us for it.

Less philosophically and more engineeringly, the advice to "trust no one" is well-founded. I mean, don't waste time trusting no one, but try not to tie your fate too closely to code you can't examine. On the grossest scale, all inter-group (much less inter-company; viz. ScriptX) projects are doomed; on a smaller one, I'd refuse to use any framework I couldn't modify, particularly after my Microsoft AFC nightmare.

(Removing and adding display elements wasn't thread-safe. OK, that's the horrible unworkable one. But the so-horrible-it-was-funny one was when I did a performance analysis and found a bottleneck at the Microsoft-supplied sorting routine. How hard is it to do a sort in an object-oriented language? There's gotta be pointers, right? I guess it depends on which sub-sub of a sub-sub gets the job, but Microsoft handed it to someone who must not've heard of pointers, and Microsoft never had the code reviewed. Christ. One routine rewritten; three-hundred-to-one speed-up.

Not nearly so bad is the temporary-object-and-synch-locking overhead of Sun's StringTokenizer. But BAD ENOUGH!)

Man. And Christ. Sometimes that English-Philosophy double major looks good.

Until I see what English and Philosophy professors are doing.

| . . . 2000-05-16 |

The twentieth century established its characteristic tone in 1901 with publication of the two sickest novels the English language had yet produced: Henry James's The Sacred Fount and M. P. Shiel's The Purple Cloud.

I don't know what to counsel for the former, but patience is counseled for the latter, since it lurches off like Jules Verne or something. Be assured: the mood then sinks like a pearl through Prell, from H. G. Wellsian to Edgar Allen Poetic and down, down, down to a really bad mood.

In the purple cloud, Shiel not only foresaw Prince's classic breakthrough soundtrack album of the 1980s but also the neutron bomb. More than forty years before Little Boy dropped, the novel described what a modern reader can only interpret as world-girdling fallout and radiation poisoning.

And what does the Last Man on Earth do after the proto-neutron-bomb delivers all that prime real estate intact into his hands? Well, what does anyone do with unlimited power? Blow things up real good! As a tribute to the eternal domitability of the human spirit, the book's only rival is Joanna Russ's We Who Are About To...; as a nightmare of premonitory guilt, I don't think it has any rival at all.

Not sure why the Bingo-Bango-Bongo-I-don't-want-to-leave-the-Congo redemptive ending didn't bug me more. Like a lot about The Purple Cloud, it reminded me of Bernard Wolfe's Limbo, which bugged me lots. Maybe it's because Shiel's version of Eve comes by her puddin'-headedness natural, having been raised by wild dust motes. Maybe it's because the relationship is played dysfunctionally enough to fit into the rest of the story. Or because the hero backslides and foreslides so often that I don't have to take his "ultimate" redemption at full CA value.... Had to end somewhere, after all. Everything does.

| . . . 2000-06-09 |

Gosh Darn the Pusher

One of the few things I don't like about MP3-mania is the way that the big software concerns have positioned it as a way to pirate CDs. I mean, what I love about MP3 is that it's a convenient cheap durable way to preserve and play audio that's otherwise available only on inconvenient or not-so-durable media: cassette-only recordings, old 45s and 78s, very out-of-print LPs.... But Real and Microsoft and MP3.com concentrate solely on making it easy for moving CD tracks to the computer, and since CDs are already pretty convenient and durable and are less likely to be out of print, it's hard not to see that as encitement to piracy.

In fact, one of the first free pieces of software that did convert non-CD-audio to MP3 files, BladeEnc, was hassled right out of binary distribution by big business monkeys. Conspiracy theory, anyone?

For alternatives, go to The Sonic Spot and Transferring LPs to CDR. My current toolkit: Wave Repair for recording and LAME for compressing.

| . . . 2000-07-04 |

Special Anniversary Narcissism Week! (resumed): Audience

From the email interview with Mark Frauenfelder: How popular is your weblog?

Beats me. I've tried to not pay much attention since the hit counts passed those of my two ancient Yahoo!-linked pages.To Paul Perry:Unless you're advertising, popularity doesn't matter on the web. That's the whole point of the web as a medium: wide distribution is cheap, and therefore not dependent on things like popularity. I know the readers who'd enjoy my crypto-cornpone style are a small minority. I just want as many of that minority as possible to get a chance to enjoy it.

I used to tell my web design students that they should count success by the amount of nice email they got. I've gotten some nice email for the Hotsy Totsy Club.

Perhaps I'm overoptimistic, but I think the distinction between community and incest is easily maintained with a little conscious exogamy. As Aquinas says, incest is sinful because its cramming together of multiple social relations "would hinder a man from having many friends." To share an interest in a form is one thing, and a nice thing. To share all the applications of that form would be incestuous if consensual; simple plagiarism if not. Which doesn't appear to be a problem in the ontogroup you've posited -- I doubt that you and I have ever had a link or a line in common, for example -- probably due to the very things that interest us in the form....Answering David Auerbach: My question to you, about writing on the web: how do you react to the choice/imposition of a very imminent and particular real audience that trumps any thought of an ideal audience?

I recognize the words you're using, but I would've used them to describe my issues with print publication. The painfully particularized audience who happens to be subscribing to a particular magazine during my particular appearance or to have bought a particular anthology containing my particular story is (precisely because it's the target audience of the publications) more than likely to be bored or annoyed by my work.Web publishing, on the other hand, is only "ideal audience." There are no promises, no presuppositions in those fluffy network-diagram clouds; anyone might bump into anything. No "ideal audience" right away? Well, put the pages into the search engines and wait. No "ideal audience" ever? Well, at least it was cheap. On the web, the non-ideal audience will simply not bother reading what I've written; that is, it doesn't exist as an audience.

The biggest problem I have with web publishing has to do with that very fluffiness -- the lack of antagonism and risk means fewer itchy stimuli to respond to, less friction to push off against, less lying but more solipsism -- which is where I'm hoping that crosslinking, email, and public discussion can help....

Although it seems to make sense that conventional publishing should lead to more topical and less personal discourse, that hasn't been my experience. In the shorter forms of paper-publishing, anyway, public commentary tends to be driven by professional feuds and personal friendships, and private commentary restricts itself to messages like "Would you write something similar for my publication?"

Books are available to a more diverse readership and thus receive more diverse reactions, but book publishing is much more big-businessy than magazine publishing, and its barriers seem well-nigh insurmountable to the easily discouraged or stubbornly erratic.

I've gotten many more direct and diverse and therefore useful responses from web publication, partly because search engines don't worry about enforcing an editorial tone, thus allowing for more startle effect, and partly because email makes it easy to send responses.

As for the cult of personality, I'd be happy to admit that I think it's impossible to separate "voice" from "content" -- at least for the kind of content and the kind of voice I have. What journalism and academia might describe as the "privileging of content" or as "self-discipline," I hear as "mendacious (if useful) voice of authority," and it makes me sick with hypocrisy when I mimic it. Scholarly and commercial venues would be accessible if I could stick to the point, and hip venues if I could stick to aggressive role-playing; but when de-emphasizing the performative and the off-putting is required for writing, then I simply don't write. And since I still seem to want to write, I make the working assumption that it's not required.

| . . . 2000-07-05 |

Special Anniversary Narcissism Week! (cont.): Technique

| The program also provides limited (exact word or phrase only) user-directed searches: |

| . . . 2000-07-06 |

|

Special Anniversary Narcissism Week! (concluded): Rooms for Improvement

Over the past year, I finished a long essay, collaborated on a short film, wrote some letters, and made a living. But mostly it's been Hotsy Totsy. Over the next couple, it won't be too big a surprise if I finish some other essays I've been promising for years (on Patricia Highsmith, on Jean Eustache...) or months (on Barbara Comyns, on Karen Joy Fowler...), or even something unexpected. And I better make a living. But mostly I expect it to be Hotsy Totsy. Well, if this is gonna be my standard watering hole, I got some suggestions to make to the proprietor, if he can rouse himself up from behind that 1.5L jug of Wild Turkey for a moment....

|

| . . . 2000-07-24 |

Juliet Clark continues her multifacetidisciplinary study of movies and/or life with "The Real Glory: A Photographic Testament to the Irresistible Glamor of a Career in the Film Industry," a behind-the-scrim look at how the cultural sausage factory inspires its pigs.

| . . . 2000-07-26 |

Zonked in a hotel room in Toronto last week, I decided that, having taken the effort to jam a folded-up newspaper into the television cabinet's door's hinge to keep it from swinging shut, I might as well watch the television. With no Black Classic Movies channel to distract me, I ended up tuning to "Survivor."

Zonked in a hotel room in Toronto last week, I decided that, having taken the effort to jam a folded-up newspaper into the television cabinet's door's hinge to keep it from swinging shut, I might as well watch the television. With no Black Classic Movies channel to distract me, I ended up tuning to "Survivor."

I'd vaguely pictured some cameras showing some people surviving on an island. Imagine my (or, indeed, your) shock on finding an elaborately artificial game show in which the "community" must eliminate one of its members each week until only one human (not counting the network spokesperson, well-fed and invulnerable in the great tradition of angelic/demonic messengers) is left sole owner of "A MILLION DOLLARS!"

This is no way to maintain a species. It's the same desperately misanthropic vision as in Joanna Russ's great novel, We Who Are About to..., except presented here, quite insanely, as some sort of model for "natural society." In real life, social success means to extend one's circle. Where else but in a television executive's mind could success be defined as reducing one's social circle to complete solitude?

In immaturity, that's where else. Children are powerless and power-hungry, and their ambitions are easily (and regularly, in most school systems) guided into the narrowest nastiest channels possible. That's one reason maturity seemed so attractive to me as a child: it seemed as if, unlike us, adults had the opportunity to be alone when they wanted to, to enjoy friendship without endless intrigue and struggle, and to leave the dodgeball mentality behind.

And I'm delighted to say that it's true! Being an adult is great! You do leave that mentality behind! What's odd -- well, "odd" is too unjudgmental a word -- is that so many inexplicably nostalgic adults seem bent on recreating it.

Don't you believe 'em, kids. Gym class isn't "like real life" unless you're a case of arrested pre-adolescent development, like some of my more severely rednecked relatives, or television executives, or

the losers on this show (link via Twernt):

"I think it's the best show out there," said Joel Klug, the salesman and health club business consultant kicked off the island in Episode 6. "Every part of America is on that show. It is us. Some people are going to band together. Some people will go on their own. Some people will have trouble stabbing other people in the back or fighting to win. It's every part of life."

"Think back to grade school," said Ramona Gray, the chemist who lasted only through Episode 4. "When you're playing kickball, picking teams, somebody always gets left out. Somebody's always going to get picked first. It happens every day to every one of us."

| . . . 2000-07-30 |

(Continuing with what Samuel Taylor Coleridge called "that gentle degradation requisite in order to produce the effect of a whole"....)

The 100 Super Movies au maximum: The Married Woman

The 100 Super Movies au maximum: The Married Woman

One of the nice things about works of art, and vacations and drugs, is that they give us delimited events to point to and say, "This -- this was the turning point. This was where my life changed," as opposed to the usual waking up to find yourself in a strange bedroom thousands of miles away with a resculpted nose and no left leg and the phone off the hook and the cops hammering on the door.

For example, I used to be pretty normal about movies. I liked them and so forth. I'd say things like "Wanna see a movie?" and then later on say things like "That was pretty good."

Then, twenty-three years ago, I went to the Temple University Cinematheque (which I guess is closed down now) and saw Jean-Luc Godard's movie from thirteen years earlier, The Married Woman. And by the time it was over, I had turned into me.

An essential aspect of turning into someone is that other people don't simultaneously turn into the same person. Even while I sat there head ringing and sparkle-eyed, comments like "Did you get that?" and "Weird!" began to worm their way through my protective daze. On my shamble out, I stopped to thank the wizened Anglophile who ran the place. "I hate Godard myself," he said, "but someone has to show him."

Yeah. Nowadays I'm just embarrassed when I see those 1960s Godard movies, but I wouldn't blame the old guy for that any more than I would blame my mom for how embarrassing it is to think about toilet training. The only one I enjoy all the way through is his comedy noir, Bande à part, which reminds me of the Coen Bros., who, like Godard, seem to have been raised in some sort of white plastic box from which they take random stabs at what real life might be like -- there's a very thin crust of experience sagging under the weight of all these violent gesticulations, a bouncing on the plywood mood that seems to work best with dimwit comedy. Of Godard's work from the 1970s, I like the TV interviews with "real people" where he sounds like Charles Kuralt from Mars; from the 1980s and 1990s, his crazy old coot self-typecasting in Prénom Carmen. The only serious Godard moments that still work are the ones where he finds himself back in that white plastic box trying to figure out why everyone looks at him funny: for example, staring into a coffee cup while taking a break from trying to show off those supposed Two or Three Things I Know About Her that, nowadays, it seems obvious to me that he never knew at all.

Not that anyone called him on it. There's no safer way for an uncool nerd to show off than by bragging about his up close and personal knowledge of women (or, safer yet, "Woman"). All those nouvelle vague guys leaned on that tactic big time; Godard, being Godard, just did so most explicitly. (As French censors realized, the title's "The" is an important part of The Married Woman's ambition.)

Not that anyone called him on it. There's no safer way for an uncool nerd to show off than by bragging about his up close and personal knowledge of women (or, safer yet, "Woman"). All those nouvelle vague guys leaned on that tactic big time; Godard, being Godard, just did so most explicitly. (As French censors realized, the title's "The" is an important part of The Married Woman's ambition.)

And, to Godard's credit as a forever uncool nerd, he was the only one of the nouvelle vague guys to try to engage equally explicitly with feminism. Unfortunately, he's also forever unable to approach female characters without interposing the clearest (and most brain-dead) demonstration of "inside knowledge": nude photography.

At the time, of course, I was more than willing to fall for such demonstrations; as an eighteen-year-old sex-crazed uncool nerd, they seemed like a darn fine idea.

And at the time, all such considerations seemed completely unrelated to what was most important about the experience, which, the next day, I inadequately described as the realization that "movies can do anything."

At the present time, my inadequate description would be that "movies can combine the discursive and the narrative."

I don't feel as comfortable with either account as I feel with explaining why they differ: It's natural for the individual who's gone through an ecstatic revelation to assume that there must be some relevance to the individual's life.

What's changed in my life is what seems relevant.

Twenty-three years ago, I probably thought of myself as someone who "could do anything," so that's how I was predisposed to understand the experience. Right now, I think of myself as someone who has to drag the discursive into every experience, so I think that the movie just happened to strike a natural-born critic.

You see, even though I promised a couple paragraphs back that I wouldn't bring blame into it, I couldn't just leave the question alone; I felt like I had to try to figure out what happened. For us natural-born critics, it's not enough to say, "My taste changed," or "Can you believe we used to like that stuff?" When we like something, it's a public statement, like pledging our troth.

Not that marriages really do last till the death-do-us part. What marriage means is that, having made a public statement of allegiance, you have to make some correspondingly public statement of divorce.

And then you get to make jokes about your ex for the rest of your life.

| . . . 2000-08-04 |

|

Like many another author setting out on a masterpiece, John Collier must have begun His Monkey Wife with the worst of intentions: to plan a romance novel whose virtuous heroine is a chimpanzee betrays a less than honorable attitude toward romance novels and virtuous heroines. In Collier's typical folderols of feckless poets and rich bullies, the female human plays the luscious main dish or the Acme beartrap but never the protagonist. And his novel, like his short stories, foregrounds a comically exaggerated ideology of misogynous sexism and Anglophilic colonolialism.

But rather than a Triumph of Arch, it's Collier's only really moving work. One of the wonders of narrative is that a story, when well-written enough (and His Monkey Wife is very well written), can be so much wiser than the storyteller. Once immersed in the point of view of long-suffering Emily, we're unlikely to be able to hold her chimpdom clearly in sight except as the primal cause of her suffering. What results is not so much a travesty of romance as one of its purest examples, complicated but essentially unbesmirched by the deadpan perversity of the humor. Our focus shifts between the extremes of expressed sincerity and implied sarcasm until the two views dissolve into a wavering, headache-inducing, but very impressive illusion of depth. By the time sex is dragged in by a prehensile foot, we are, like Mr. Fatigay, more than ready to succumb. I think Emily Watson for the movie role, don't you? |

|

Bestiality has never seemed particularly profound in Real Life, but, since Robert Musil's quiet Veronika was first tempted by her Saint Bernard, it's been a sure-fire booster of moral complexity in Fiction.

Sex can work heavy-duty alchemical action on even the shallowest of animal fables, as proved by the only good thing ever written by hack libertarian and Welsh-supremecist Dafydd ab Hugh, "The Coon Rolled Down and Ruptured His Larinks, A Squeezed Novel by Mr. Skunk." Again we find the ambition-performance ratio unexpectedly reversed. In ab Hugh's story, zero-sum economics applies to intelligence: as one part of society gains IQ, another part accordingly dumbs down, which is why democracy can't work. If he'd illustrated his postulate with, say, American ethnic groups, he might have had some difficulty selling his story to a genre magazine. And so he uses the slightly less controversial hierarchy of species. Which is how he ended up with something more sellable and richer and stranger than he could possibly have imagined. No matter how fleabit and fanatic, cute fuzzy hungry animals can't help but gain our sympathy; a taboo against "love in the streets" can't help but predispose us to cheer on an affaire de coeur between underboy and underdog, no matter how disgusting. So, even though the story (mercifully) doesn't work as propaganda for ab Hugh's political position, his viciousness does manage to keep this Incredible Journey from falling into Disneyesque propaganda of another sort. Thus muddling doth make heroes of us all. |

| . . . 2000-08-18 |

|

Cholly on Software On Managing Software |

| Goddamned kindergarten world |

|

My geekiest college friends lived together one year off-campus, in a condo-like complex rented out both to students and to real people with families and jobs. Which could be rough on the real people, families, and jobs. Once when my geeky friends were coming home, probably while working out all possible variants of a Monty Python sketch, they met one of their neighbors leaving for work; as respective doors closed, they heard him mutter "Goddamned kindergarten world."

I used to think that I'd wind up as one of those sweaty guys you see pushing their way around the city muttering nonsensical obscenities nonstop under and occasionally way over their breath. But now I'm starting to think maybe I'll wind up just muttering "Goddamned kindergarten world" nonstop instead. Or, what do you think, maybe I could do both? Like, one mutter for interiors and the other for commuting? |

| . . . 2000-08-20 |

There's no denying the mythic catchiness of Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe. And there's no admitting his possibility. Just where would a glib dumb prissy pushy tall dark handsome breast-beating alcoholic intellectual low-brow heterosexual urban nostalgic two-fisted prose stylist idealist spring from? Los Angeles? Regretfully, no. And how would he make a living? As a private detective? I think not. Marlowe can only be explained as a self-loathing writer's pastless futureless power fantasy, who springs only from a book and makes a living only in books.

Which entices moviemakers into a dried river bank surrounded by giant ants, n'est-ce pas, cherie? Movies are supposed to be able to handle detectives; it says so right here in my Popular Culture Handbook. But how can the movies straightfacedly present such an unjustifiable character? ("With Cary Grant" is the best answer, but Chandler didn't manage to talk the studio into it.)

The first successful Chandler adaptations saved themselves by keeping some snappy lines and imagery and ditching the leading man: Edward Dmytryk's "Marlowe" reverts to sleazy Hammett-style professionalism and Howard Hawks's "Marlowe" anticipates James Bond's irresistable aplomb.

Less successful as film but more interesting as critique, two later adaptations tossed out the easy stuff like Chandler's dialog in favor of Chandler's essential oddity. Proving again that hostility towards one's source material is the healthiest stance for a director, Robert Altman's attempt to destroy Marlowe is cinema's first real tribute to the character. The Elliott Gould "Marlowe" could be an aging trust-fund kid who's retreated into fantasy, but there's no way of knowing for sure; the movie preserves his inexplicability while giving it a believable presentation (this Marlowe is as passive, inarticulate, threadbare, and isolated as most self-deluded personalities) and environment (this Los Angeles is too universally self-absorbed to take notice of any particular citizen's delusions). And Sterling Hayden's towering and toppling "Roger Wade" is just the self-loathing powerful writer to shove the Chandler subtext explicitly into our face and down our throats where it belongs.

The only movie ever influenced by The Long Goodbye was The Big Lebowski, a hoot-and-a-half in which Altman's ego-gored hostility is replaced by the Coen Bros.' aimless playing around. Since Jeff Bridges' character pretty much shares their attitude, the result is the most warm-heartedly engaged take on "Philip Marlowe" yet, even if there's not much Brotherly affection left over for any of the other characters....

For a long time -- like, a really long time, let's not even go there -- I've dreamt about my own fully explicated version of a Chandler detective: he's a paranoid schizophrenic who's assigned cases by the voices in his head and whose secretary / leg-man is his pet parakeet. But I have a hard time writing fiction so I've never committed this dream to print. Probably just as well.

Perhaps a similar dream prodded at young Jonathan Lethem, who came up with an admirably tailored science-fiction-y explanation for the Chandleresque narrator of Motherless Brooklyn: Tourette's syndrome. The gap between the narrator's careful prose style and his hit-me-harder banter? Tourette's syndrome affects speech and not writing. The narrator's weirdly monastic dedication to the case? Tourette's syndrome is associated with obsessive-compulsive behavior. His inability to sustain a sexual relationship? Say no more. If anything, it's too well-tailored: even the narrator eventually notices the snug fit, but, of course, is able to explain that explaining his every trait as a symptom of Tourette's syndrome is actually just another symptom of Tourette's syndrome. Clothes make the man if you're selling clothes, syndromes make the character if you're selling pop psychology, but a novel's air gets kind of stuffy by the end....

Which also counts as a Chandleresque effect: Chandler's The Long Goodbye was more like The Long Squirm in a Pinching Suit (but in an interesting way, if you know what I mean), and I could never spend more than a couple of minutes in Playback without rushing back outside for a breather....

| . . . 2000-08-25 |

A Musical Interlude

Doug Asherman says that "Cuba Solidarity: Send a Piana to Havana" "don't know why, reminded me of you. Maybe the rhyme?"

Doug Asherman says that "Cuba Solidarity: Send a Piana to Havana" "don't know why, reminded me of you. Maybe the rhyme?"

Could be, 'cause my only real knowledge of Cuban music is from when we were stationed at the US military base in Guantanamo Bay and I obsessively played a Roger-Miller-ish novelty single whose chorus went:

Cuba, Cuba, Cuba is my home.

Cuba, Cuba, Cuba is my home.

Fidel Castro, don't you pout,

Six more months and I'll be out.

Cuba, Cuba, Cuba is my home.

And I suspect that Beth Rust sent me the following because my own nose was once such a growth industry, although it seems to have stagnated for the nonce:

Believe it or don't, I picked up a CD of Johnny Crawford's -- remember him? The Rifleman's doe-eyed son. According to the amusingly matter-of-fact liner notes, he got coerced into a brief career as a teen idol, having "a pleasant tenor voice". He apparently quit the biz as soon as he got out of high school and went off to be a rodeo cowboy, but no matter how tough he gets there will always be "Your Nose is Gonna Grow" as a reminder of his rebellious youth. "No One Really Loves" (a clown) is a bit on the edgy side for Johnny, but I think he handled it well.I did a quick check for Crawford web sites; this one's "unofficial" but apparently condoned. I was astonished to find that the guy is running a big band now... There was also something about a new movie, the entire cast of which appears to be former child stars (it is, of course, science fiction).

| . . . 2000-08-29 |

"a specialized shop, department of a store, etc., usu. catering to fashionable clients"

Pamphleteer Juliet Clark writes:

Pamphleteer Juliet Clark writes:

Re the Salon.com Guide to Feeling Hip Because You've Heard of John Updike:And David Auerbach weighs in more fatalistically:I'd like to point out that Eggers misspelled "aficionado," and the copyeditor didn't catch it.

I think your copyediting/programming analogy is apt in a lot of ways. In fact the whole Salon Guide reminds me to a painful degree of startup culture: young people who won't be young much longer demanding to be taken seriously for not being serious; seeking the Big Time while clinging to a fantasy of countercultural identity; using strained irony, self-created urgency, and an excess of spin to mask a fundamental laziness.

All I can suggest is that you sell your author copy and use the money to buy a good book. Wouldn't that be, like, "ironic"?

I do think that the Salon guide fills a void. We currently have no one to tell us which of the many, many idiomatically similar novels are the real thing and which are the product of overheated middle-class ramblings. The academics can't be bothered with it, since they're too busy keeping their own little flame alive. People like Lewis Lapham hate it all, and people like Michiko Kakutani are either indiscriminate (if you agree with them more often than not) or too harsh (vice versa), and they lack consensus-building skills. The remainder of the book-reviewing populace don't have enough credibility to be reliable. So I think contemporary mainstream book reviews, if there's a strong enough drive to hold people's interest, will go the way of movie reviews and devolve into capsule reviews, top ten lists, and "personality-based" reviewers. I don't think I can blame anyone for this process; it just happens when the collective standards of the producers and the consumers are low enough that the work being produced becomes undifferentiated.Oh, I don't really blame the Salon editors; I imagine it's pretty hard to resist the temptation to milk the cash cow when it's looking up at you with those big brown eyes. I just wish I hadn't seen the result. And I probably wouldn't have if the usual uncentrifugeable muddle of curiosity, vanity, and sense of responsibility hadn't talked me into becoming a contributor.... Being a critic, of course, although I blame myself, I attack them.Consequently, tho, Carol Emshwiller will certainly be ignored, and even someone like Disch, who has needed to work his material into ostensible potboilers for the last 20 years. There is a need for something of a unified conception, and Carol Emshwiller may as well be Les Blank for all they care. (Which might make Michael Brodsky Kenneth Anger.) There definitely is a "celebration of shared limited knowledge", but who were the Salon editors to deny those who looked towards them for guidance?

If Auerbach's right about the editors' ambitions, the match was doomed a priori, since I'm even less of a consensus-builder than Michiko Kakutani. (Case in point: For the last twenty years every single time I've tried to read the NYTBR I've ended up throwing it across the room, and so I didn't even recognize her name.) When it comes to art, I don't see that consensus is necessary, or even desirable. That's probably what attracts me to the subject: I wouldn't be so exclusively an aesthete if I were a more enthusiastic politician.

One clarification / pettifoggery as regards "personality-based" reviewing: It's true that I believe a critic can only speak as an individual, and that criticism is most useful when individual works receive close attention as individual works. That means that I consider generalities issued from a presumed position of consensus to be bad criticism. It doesn't mean that I consider class-clown-ism a guarantee of good criticism. In my Salon.com tantrum I emphasized voice because voice was being emphasized by the book's publicity and reviews, but what really set me off was the 400-page-long lack of new insight into individual works: a generic free-weekly voice was just the means to that dead end.

In my own practice I use an overtly performative voice only because I have to. When I attempt a detached tone, I become too stumble-footedly self-conscious to move; when I do the jutht a darn-fool duck shtick, life seems better. That's a personality flaw, not a deliberate choice. Behind the Dionysian mask, I'm ogling those Apollonians plenty: I empathize with Jean-Luc Godard's film criticism but I'm in awe of Eric Rohmer's; Lester Bangs is a role model but I'd be so much more uncomplicatedly proud of something like Stephen Ratcliffe's Campion; my favorite Joycean is eyes-on-the-page Fritz Senn; my favorite historian is no-see-um Henry Adams; I loathe the bluster of Harold Bloom and Camille Paglia....

What matters is whether you communicate anything of what you see. If you don't have to keep twitching and waving and yelling "Hi, Mom!" while you do it, all the better.

| . . . 2000-09-09 |

To unclench our previous entry on the transformation of Insider Art to Outsider Art....

The process can always be side-stepped by looking at artifacts as History: History, like Cheese, is capable of digesting all. But inasmuch as we try to keep our receptiveness aesthetic instead of historical -- focused on surface pleasure rather than background book-larnin' -- when faced with an artifact imported from outside our assumed position, narrative impulse veers us towards seeing the alien context as the alienated individual and the artist as Outsider (rather than ourselves as Importer).

Some examples:

And unless you're talking bestsellers and movie deals and posters on bathroom walls, it's awfully hard to be sure you've made it off an insular group and onto the mainland. "Professional" or not, in my cartography, the arts and book reviewers of the semi-major media look just as self-congratulatory and determinedly deluded as any communal gallery, small press magazine, indie rock scene, little theater group, or crosslinking weblog....

| . . . 2000-09-16 |

Errata

As a certified holder of a Bachelor of Mathematics certificate, I can confidently assert that rationality exists only as a way to juggle all the words one feels compelled to throw into the air. But even that certificate is no guarantee of success, and the Outsider Art go-round left a hatchet, a raw egg, and a beach ball on my face.

Most of the muddle was caused by my smudging across questions of production (what do we notice? what attitude do we take? what markets do we approach?) and questions of consumption (how do we notice? how do we understand? how do we enjoy?) as if all of 'em were one big really dumb question.

Thus, Doug Asherman points out that I claim that the worst thing is the formation and mutual support of a mediocre group, when the really REALLY worst thing is when the mediocre group manages to convince larger groups to take it even more seriously than it takes itself.

Regarding "insularity," David Chess suggests

that there is no "mainland" at all, except in the sense of a particularly large (or visible, or well-funded, or populous) island.(In fact when we're talking The New York Review of Books it's not even that large an island; it's just that the islanders think it's centrally located.... Minifesto: I'm not sure that a decentered self is necessary for ethical living, but I'm pretty sure that a decentered self-image is.)

And giving David Auerbach the last long word:

With all respect, I want to reframe your insider/outsider argument, because

I'm not eager to see another generation of writers inspired by Colin

Wilson's The Outsider willing themselves into solipsistic states of media

attention and minor celebrity. I'd like to displace the insider/outsider

dichotomy into the realm of 'material'. There's a quote from John Crowley's

review of Lanark that I'm thinking of:

But the outsider brand, in its two forms-- --From without-- The Jack Spicer bit is priceless, but all those "Crazy Buddhist art. Crazy Hindu art. Crazy Medieval German art." fall more under the rubric of exotica rather than "outsiderism," I'd say. What the two have in common is a desire to attach the label of foreignness to the work. I think this is less a narrative conceit (as you say) than an impulse on behalf of both the producers & consumers to mythologize & escape. And it's going on contemporaneously too: what Richard Ford & David Foster Wallace have in common is a mythologizing of everyday materials, albeit in very different form. It's not very good mythologizing (Richard Yates did it best, and most honestly, in my view), but it's still an updated variant on what Mailer, Updike, Oates, and the rest of those geezers have been earning accolades for for years. The dominant short story paradigm in most of the anthologies these days seems to be (1) the "I'm so real" Carver-derived approach of Tilghman, Offutt, and many others whose names I've forgotten, or (2) the creepy, sub-supernatural angstploitation of Lorrie Moore, Ann Beattie, David Gates, and I suppose Russell Banks. Both are variants on the same impulse to impose a private "outsider" view on ordinary materials through sheer will -- because that's the only thing that can make it worthwhile. It's a lousy approach. I think the consequent turn to the exotic stems from the same cause -- when people get fed up with the fakery of the above, they turn to the irreducibly foreign. And then there's people like our friend Jandek who apparently achieve some level of commodification by being fetishized by collectors, and the ensuing debate over whether he and others are the "real [foreign] thing" or not. It's very important to the consumers that they are -- what could he possibly have to say if he were just like you and me? Granted, I think America (north and south) is more prone to mythology than the Europeans or Asians (hence our great legacy of comic books & comic strips!), but the current crop of writers is too civilized to do it honestly. So while they're too self-conscious to apply the label to themselves even as they incorporate it into their fiction, those who feel it... --From within-- still don't use it as a primary marker in their work, though they may try. I look at Bruno Schulz's work and compare it to Beckett's, and while I see them trying for similar effects, I think Beckett is more successful. This despite Schulz's Kafka-like isolation and Beckett's (relative) integration into the various scenes around him. I'm tempted to see the issue, then, as irrelevant to the quality of the work being produced -- though it may just be that Beckett was just such a prima facie genius to everyone around him that he could have been totally maladjusted and still fit in. Thomas Bernhard, on the other hand, is a writer who I think really hurt his work by being so socially involved in Austrian theater and politics, but I don't think that it was socialization per se that damages his books so much as an innate desire to throw obscene epithets at other people. With or without the opportunity to hurl them from a respected position in Austrian letters, I think his work would've suffered the same. |

| . . . 2000-09-28 |

Movie Comment: The Brandon Teena Story

| "I wouldn't live there if you paid me to." - David Byrne |

"thinking: I didn't leave them like that! I didn't. It's not real." - Samuel R. Delany |

The fifty students in my class maintained their allotted Kinsey percentages, but homosexuality by definition didn't exist. The few kids who were active deviants were probably as active as they were only because they were already established as pariahs -- and even they were invisible to all but an inner group of their peers. As a fairly trustworthy peer who'd come from and who was obviously back on his way to "the outside world," I got to talk to a couple of kids whose confusions were particularly pressing. The town seemed (and seems) to me far too dangerous and confusing an environment for either gay or straight sex, and so I always advised caution in leaping to conclusions -- or, for that matter, leaping to anything, though wuddya gonna do? it's teenage hormones.

The kids who later on did get out of town incorporated new experiences and self-definitions in a dazzling variety of ways, some of which involved familiar labels and some of which didn't. The ones who stayed continued to live in a world that included revolving-door marriages, suicides, alcoholism, beatings, and fatal accidents, but not homosexuality. Sexual surveys of the people in town and the people who'd left would give you very different results, but inasmuch as you learned anything of value it wouldn't be about innate sexuality: it would be about the social effects of monoculture.

I believe that a moral imperative for narrative art (including discursive prose) is to present the "strange," the "peculiar," the "monstrous." Not in the professional ooh-aren't-we-naughty fashion that justifies the status quo with supposedly "dangerous" material rather than supposedly "safe" material, but in a way that, whether angry or affectionate or panicked or flat as a pancake, somehow does what it can to prepare its audience for "the outside world."

Of course, all this only matters because there's more than one "outside world" and more than one "monoculture," and as we make our transitions between them the moral imperative can start to get pretty contorted.

The other night I saw The Brandon Teena Story and saw depicted -- pretty much for the first time in a movie -- the familiar landscape, accents, mannerisms, faces.... About as intense a bad nostalgia trip as could be imagined. Just like going home too late to stop something.